Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Yes, you can use the Memory Palace technique without visualization.

Yes, you can use the Memory Palace technique without visualization.

I’ve been doing so for years as the founder of the Magnetic Memory Method. I’ve also succeeded beyond my wildest dreams as someone who experiences very limited visual imagery.

At first, I struggled with this technique, however. Until my research revealed that the Memory Palace technique was never purely visual.

No, from the beginning, the technique was taught in multi-sensory ways, including one powerful approach that is purely logical and conceptual.

And that’s the approach that helped me earn my PhD in Humanities at York University.

It also helped me learn languages, pass multiple certification exams and substantially expand my knowledge base.

And I’m not alone.

Today, accomplished memory athletes with no “mind’s eye” (aphantasics) prove that Memory Palaces work without inner pictures.

So how did the technique get mischaracterized as primarily visual? And how can you rapidly create well-formed Memory Palaces in just minutes?

Whether your imagination produces high-definition images or nothing at all, the methods I’m about to share will help you use the Memory Palace technique to learn faster and remember more.

Let’s dive in.

Why Visualization is Incorrectly Emphasized in Memory Palace Training

If you’re new to the Memory Palace technique, its ancient roots might not be on your radar.

Yet.

But we know from the historical science writer Lynne Kelly in books like The Memory Code and The Knowledge Gene that this technique had non-visual foundations for thousands of years.

For example, humans “offloaded” information they needed to remember onto rocks arranged in particular ways at sites like Stonehenge.

People also used objects covered in beads called lukasa to feel where they had encoded information in space.

As the Aboriginal author Tyson Yunkaporta shares in Sand Talk, elders used their hands as Memory Palaces. In some cases, they used each finger to remember an individual rule of conduct during a meeting.

Rather than visualize anything with the mind’s eye, bringing the thumb together with a particular finger sparked recall.

And these are all examples of the Memory Palace technique using an approach that is not inherently visual. It is spatial, kinesthetic and conceptual.

Fast forward to the Ancient Greek and Latin memory tradition, Simonides of Ceos emphasizes location as a concept above all things.

And St. Thomas Aquinas insisted his students imagine that they were inscribing information into the walls of their Memory Palaces as if writing on the surface of a wax tablet. He borrowed this idea from Aristotle and extended it with other useful ideas I have covered in this tutorial on Aquinas and memory.

So how did visual imagination come to be so prominent?

Misrepresentation by Modern Interpreters

In 1966, Frances Yates released an important, but deeply flawed study of the technique called The Art of Memory.

Don’t get me wrong. As a history of various mnemonic devices, it’s an important work. It has also inspired thousands, if not millions, of people to give memory techniques a try.

That said, we shouldn’t brush the problems she introduced under the rug.

By her own admission, she never actually used the techniques she wrote about.

As a result, she missed the importance of orientation, physical sensation and conceptualization discussed multiple times in her historical sources.

How was this mistake possible?

Besides not actually trying the techniques, I believe Yates may have been influenced by Dorothea Waley Singer.

Although this point might seem like an unnecessary detour, bear with me. It will pay off.

In 1950, Singer published the first edition of Giordano Bruno: His Life and Thought.

Singer’s biography influenced and inspired Yates’ own book on Bruno. Yeats in fact wrote The Art of Memory as background for her own book on the infamous mnemonist.

Here’s the problem:

Singer utterly dismisses the influence of another mnemonist named Llull on Bruno. She in fact suggests that Bruno was an utter fool for tinkering with Llull’s memory wheels.

So you don’t think I’m exaggerating, here’s exactly what Singer says:

Capable of hero worship, Bruno sometimes chose heroes who would have been strangely out of touch with him, as for example that saintly and mystical, muddled and truculent Franciscan, Raymond Llull, on whose worst works he wasted many years.

I wish the joke was on Singer and Yates. But it isn’t. Their mistaken dismissal and failure to deeply explore the techniques led a major problem to spread everywhere.

Due to Yates’ enormous influence in particular, uncountable numbers of people have misunderstood the non-visual art of combination so necessary to effectively using Memory Palaces.

As you can learn from this tutorial on Giordano Bruno, he wasn’t wasting his time on Llull at all.

Far from it.

The Influence of Memory Competitors & Stuntmen On the Mass Market

I’ll never forget when one of the most successful authors of memory books told me, “Whatever you do, don’t tell them about the science!”

This was Harry Lorayne, an influential popularizer of memory techniques like linking, the Major System and the story method.

Sadly, Lorayne believed that most people could not rise to the challenge of learning the most robust methods available (like the 20 memory techniques I describe in this tutorial).

He also thought that using memory science to prove that the techniques work only caused eyes to glaze over.

Although Lorayne may have been right that many people just want a fast solution to their memory problems, my point is that he and many other memory teachers took shortcuts.

Rather than lay out all of the multisensory, Lorayne went so far as to cut the Memory Palace from his training until his final book, Ageless Memory.

For years, he stubbornly insisted that he didn’t use Memory Palaces despite all evidence to the contrary. I give some of that evidence in this tribute video I made about Lorayne following his passing:

On top of constantly using words like visualization and teaching people to see pictures in their imagination, Lorayne created the impression that Memory Palaces weren’t needed at all.

Another influential memory improvement author named Tony Buzan avoided this error by carefully detailing both Memory Palaces and multi-sensory mnemonic imagery.

But like Lorayne, who was a kind of stuntman of memory, many memory competitors flooded the market with books that refused to challenge readers.

Nelson Dellis is one of the few exceptions to the rule. As a 6x USA Memory Champion who openly teaches how to beat him, Nelson once remarked during a Magnetic Memory Method Podcast interview that “there’s no time to visualize” while using Memory Palaces in the heat of competition.

Despite my efforts in speaking with people like Nelson over the years, it’s been an uphill battle.

And when you combine the force of Lorayne’s influence with Yates, it’s easy to see why many people wound up misunderstanding how our ancestors actually used these techniques.

As a result, they’ve unnecessarily struggled and memorized much less information than they could have otherwise.

But there’s one more factor we need to consider, perhaps the most serious of all.

The Real Problem: People Falsely Believe They Need “Pictures”

Back in 2015, countless people started emailing me about a condition they called aphantasia.

Originally, I dismissed the idea because I know exactly what it’s like to live with seeing pictures in my mind.

But after finally learning about a study called Lives Without Imagery, I got seriously concerned.

People were now using a “condition” labeled by psychologists to describe why they were struggling to use Memory Palaces.

Given that Lynne Kelly identifies as aphantasic and still performed well at memory competitions and as a mnemonist, there’s a clear and obvious disconnect here.

Don’t get me wrong. Some people do benefit from visual memory skills.

The point is that you don’t need them to use the technique.

In fact, many people without aphantasia struggle to imagine clear visuals.

Personally, I feel like people trick themselves into mistaking how we describe the imagination for a proper definition of mental imagery as it is actually experienced.

I’ve written this complete discussion of mental imagery if you’d like to better understand the distinction.

When it comes down to brass tacks, I don’t know how to make the point clearer than this:

The belief that imagery is required for success with Memory Palaces blocks people from using the technique authentically.

The Multi-Sensory and Conceptual Alternatives

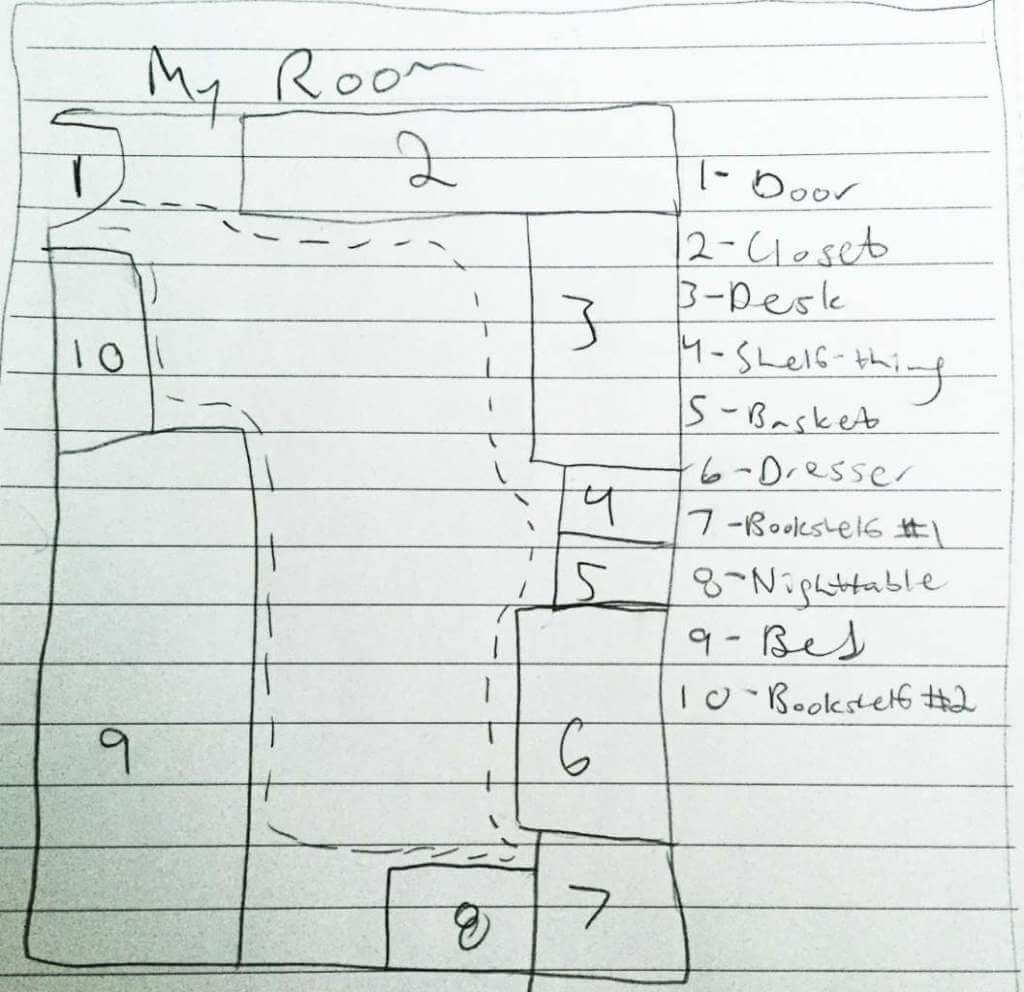

As you’ll discover in my full Memory Palace tutorial, my main suggestion is that people make the process inherently visual through the kinesthetic process of sketching.

Over the years, I’ve received thousands of Memory Palace drawings from students of the Magnetic Memory Method Masterclass around the world.

These Memory Palace examples completely eliminate the need to imagine the location visually. Instead, you physically produce it so you can see the plan with your physical eyes.

This key distinction made it possible for me to start using the technique immediately after a period of struggle.

I only came to the idea of drawing my Memory Palaces after reading a book by Robert Fludd and speculating that he and other early authors of Memory Palace books must have sketched the illustrations for their printers.

When I discovered how helpful this simple step was, I added simple sketching to other aspects of memory techniques.

For example, I started sketching rather than using words on my flashcards and then combining them with my Memory Palaces. To take just one of many examples, I passed level III in Mandarin easily as a result back when I was learning Chinese using this approach.

Even if you’re highly visual, I still encourage you to sketch your Memory Palaces.

Not as art.

But as a simple planning step to avoid leading yourself into dead ends and creating other avoidable issues.

I’m still proud that my fellow mnemonist Jonathan Levi came to me for advice when preparing to memorize his TEDx Talk.

He’s very visual, but still benefitted from the exercise. He even shared the MMM-style Memory Palace in the talk itself:

But there’s more than one way to use the kinesthetic mode to help you experience the Memory Palace technique.

Let’s explore further.

Kinesthetic Loci

When using the method of loci (an alternative term for the Memory Palace technique), you can make the experience more physical in a few different ways.

I’ve used each of these approaches:

- Run your hands along the walls of a location to make the journey firmer in your mind.

- Imagine doing something physically at each station in the Memory Palace, such as bending down to tie your shoes by the door, brushing your teeth next to a plant, etc.

- Reach up mentally to touch the top of a bookshelf (something suggested by Peter of Ravenna back in the 15th century).

- Associate various locations with gestures, such as waving hello at an entrance.

As an exercise, quickly sketch your home and then run through each of the tactics I just shared.

Don’t try to visually imagine the Memory Palace.

Literally examine your own sketch with your eyes as you experience the location visually with your eyes and then feel the sensation of tying your shoes or making a physical gesture.

This will start training your mind to approach the technique in a deeply physical way.

Auditory Loci

Next, practice anchoring various points in your Memory Palaces to sounds.

Imagine:

- Hearing footsteps in a hallway.

- The echo of voices in a stairwell.

- Music playing from a bedroom.

These are all associations that occur naturally in these locations.

Also practice strange soundscapes, like imaging massive church bells ringing in a tiny bathroom.

As you explore this form of Memory Palace creation, limit the scope of your focus as closely as you can to pure sound. Doing so will exercise your auditory memory at the same time you build your Memory Palace skills.

Abstract Loci

Although it’s not always practical for use in learning when exams are at stake, you can stretch your skills quickly by experimenting with abstract Memory Palaces.

For example, watch this tutorial on using Geometrical Memory Palaces:

Again, you don’t have to “see” anything.

Whether you’re using a square, circle or more complex shape, words alone will help you navigate from corner to corner.

Conceptual & Logical Loci

Some of the most powerful techniques are admittedly a bit challenging to understand.

My favorite are found in the work of Jacobus Publicius, who was massively influential on Giordano Bruno. Perhaps even more so than Ramon Llull, something neither Singer nor Yates seem to have picked up.

This approach involves using a lot of categories, oppositions and logical frameworks as spatial anchors.

For example, Publicius teaches us to think purely in terms of the cardinal directions (north, east, south, west).

He also discusses alphabetical arrangements on squares and wheels that are navigated directionally by looking at the diagram, not in your imagination.

This one, for example, is a physical volvelle with rotating parts that get your hands involved in the encoding process:

You also find in the ancient tradition a lot of combinatorial tables that work like logical slots.

One way I’ve used pure logic in combination with Memory Palaces has helped with picking up new languages.

Opposites, for example, are logical. You can place the word for “white” on one wall and the word for “black” on another. Provided you use the technique consistently, you can memorize a lot of vocabulary quickly in this way.

Think of it like this:

A location is not just something you look at.

It’s a system of relationships involving everything from facts about height and weight, to grades of light and shadow at various times of day.

The more you think about the logic of association, the more you can harness these conceptual aspects. And the command to “think” has long been part of the tradition, something demanded by Aristotle, Hugh of St. Victor, Peter of Ravenna, Jacobus Publicius and many more.

Perhaps Bruno’s demand to think reached the highest crescendo when he suggested that anyone who thinks long and hard enough about the Memory Palace technique will reach the same conclusions about it as he did.

In Tony Buzan’s The Memory Book, specifically what he called SEM3, we see this principle in play.

Although you might not need to go to these conceptual lengths for your own learning projects, the point is that none of them require you to visualize.

The Integration Principle

The key is never to rely on just one approach.

As taught by Hugh of St. Victor and many other mnemonists until the 20th century, you want to approach all aspects of mnemonic technique in a hybrid manner.

Especially the Memory Palace, as stressed by St. Aquinas long ago with his suggestion that you imagine writing your mnemonic associations into the walls. Literally feeling and hearing the process as you go.

Practical Walkthrough: How to Build a Non-Visual Memory Palace

When you’re just getting started, here’s how I recommend you proceed:

- Choose a familiar location that doesn’t require the strain of trying to visualize it. The place you’re in while completing the exercise is a good option because you can see it in front of your eyes.

- Sketch out the floor plan using pen and paper, not software. Some people do like to use various computer programs and even virtual Memory Palaces, but resist this for now so you don’t place an interstitial screen between your mind and memory at this point.

- Assign each station using a variety of the methods described above using the Integration Principle.

- Rehearse the Memory Palace in all of the patterns I teach in my spaced repetition tutorial.

- Pick a learning goal and use multi-sensory associations on each station to encode the information. Start simply with the number rhyme technique if you want the easiest approach to encoding as a beginner.

- When retrieving information, focus on physically navigating the Memory Palace as if you are participating in a theatre play, not replaying a movie.

This final practice step is crucial.

Many people try to re-enact what happens in their Memory Palaces perfectly, as if reviewing a movie.

That’s not possible, and it’s also not necessary. The Memory Palace technique is much more like theatre where the actors always do things differently.

They still give you the target information, but never in quite the same way.

In other words, approach your recall practice in a relaxed manner that allows for difference. They will always be there as part of your practice with this technique.

Advantages of Non-Visual Memory Palaces

If you’re already skilled with Memory Palaces, you’ll soon find many benefits from reducing down to other modes of experience apart from the visual.

For one thing, you’ll recover the true historical breadth of this mental art.

You’ll also likely find that logic-based loci and associations are more durable than fleeting images. This is because they’re typically easier to dimensionalize.

You’ll also enjoy deeper personalization and variety, which we know from studies in active recall help many learners recall more information with greater accuracy.

Examples & Case Studies

As already discussed, memory experts like Lynne Kelly have used memory techniques with great success without having inner images.

Kelly in particular uses a lot of the ancient memory techniques we’ve just gone through. Her book Memory Craft is fantastic for more information and notes from her personal practice.

Keeping in mind that I’ve already broken the advice from Rhetorica ad Herennium that the teacher of memory should give no more than two examples, let me detail one of the most direct case studies.

Bruno’s Body Memory Palace

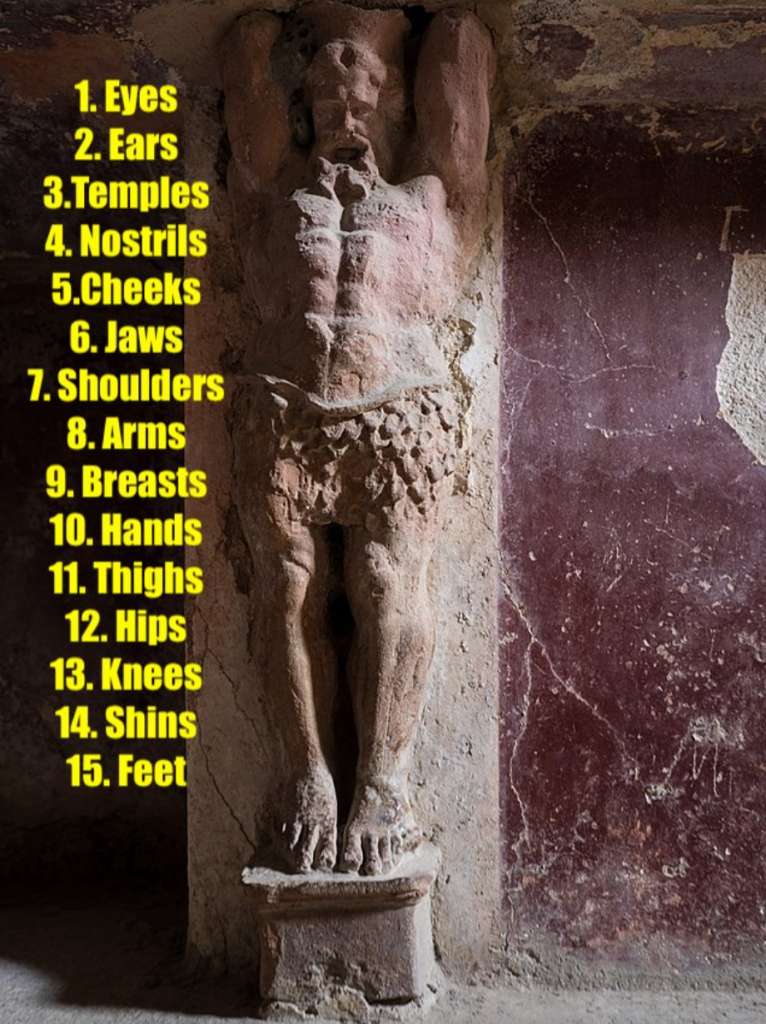

Your own body is one of the most physical Memory Palaces you can use.

In Bruno’s case, he talked about creating 30-station Memory Palaces on the statues of mythological figures.

To get that many stations, he focused on all of the major body parts that come in pairs, like the eyes, ears, cheeks, hands, etc.

If you try this practice, your Memory Palace might look something like this:

You can easily start by applying this approach using the journey method to your own body.

I personally start from the top of each body (or my own body) and work my way down. You might prefer to start from the feet and work your way up.

Either way, note that you don’t have to assign as many stations as Bruno advised in his 1586 book, Lampas triginta statuarum (The Lantern of Thirty Statues).

For example, in his Black Belt Memory course, Ron White shares a 10-station version. Not only is this reduced number of stations more practical. He also shows how you can easily link each station to the Major System.

My Hand Memory Palace

My personal favorite use of a physical Memory Palace was a hand Memory Palace I assigned in preparation for an interview with Tyson Yunkaporta.

You can see me use it in the video version of our discussion:

Although the list of steps for holding a meeting I memorized based on Aboriginal tradition was brief, using my hand was a lot faster than the way I normally memorize lists.

On each finger I placed a single word:

- Connect (pointer)

- Respect (middle)

- Reflect (ring)

- Direct (pinkie)

To lock in each word, I used a phonetic and logic-based version of the pegword method to lock in simple associations on each finger.

For “connect,” I imagined the singer Connie Francis on my pointer finger, Aretha Franklin singing “Respect” on my middle finger, and so on.

It was easy, fun, fast and required no visualization whatsoever.

FAQs About Non-Visual Memory Palaces

I’ve been blessed to receive countless questions about memory techniques over the years, either through my contact page or through one-on-one memory coaching.

Here are some rapid fire responses to the most common questions I’ve received.

Do Memory Palaces work if I have aphantasia?

Yes, and in many cases they work even better because having to visualize takes more time and mental energy than necessary.

What if my imagery is inconsistent?

There are two points to consider:

First, “imagery” is not quite the right way to look at mnemonic associations. So long as you practice using phonic similarities and logical connections, you don’t need imagery at all.

Second, as I discussed above regarding thinking of Memory Palace as theatrical rather than cinematic, our associations are bound to be inconsistent.

It’s not a problem so long as you approach the technique with realistic framing.

Why do people say that the Memory Palace is a visual technique?

Many people have been influenced by authors like Frances Yates and Harry Lorayne.

In reality, the Memory Palace technique was never strictly visual.

Having read vast amounts of ancient memory improvement guides, I believe our ancestors would be distressed to see how some of the most important aspects of the technique have been deemphasized.

That said, if you read teachers like Hugh of St. Victor, Peter of Ravenna and Giordano Bruno, you’ll quickly see that their students also came to them with incorrect conceptions.

There’s a particularly funny passage in Ravenna’s The Phoenix where the author corrects the limited mindset through an example of a typical student objection. You can read it in my updated version of this classic memory training book, available from the Magnetic Memory Method products page.

What senses can you use other than vision in a Memory Palace?

The main eight “Magnetic Modes” I use have come to be called KAVE COGS.

This is an acronym for:

- Kinesthetic

- Auditory

- Visual

- Emotional

- Conceptual

- Olfactory

- Gustatory

- Spatial

I don’t always use all eight. But sometimes I dig deeper into the conceptual mode, which has twenty variations. I shared some of them above in terms of category, opposites and the cardinal directions.

Generally, these are best saved for really tough information, like the Sanskrit phrases I’ve memorized.

Do non-visual Memory Palaces take longer to build?

When you follow my simple sketching recommendations, no. In fact, the process is much faster.

That said, the amount of time depends on the learning project.

For my Sanskrit memorization goals, one Memory Palace took a few extra minutes to work out.

This is my drawing of this particular Memory Palace, which I pre-numbered to help me also remember which verse I memorized on the individual stations:

But generally, a well-formed Memory Palace takes 2-5 minutes to develop or less.

Can I combine the Memory Palace with the Major System without visualization?

This is a very important and interesting question.

In fact, the Major System is a kind of Memory Palace.

So too is its extension, something called a 00-99 PAO System.

The reason I suggest you consider these tools as types of Memory Palaces is simple:

As Hugh of St. Victor pointed out in his writings on memory (which you can find in The Medieval Craft of Memory), raw numbers create a kind of field.

I’ve created this illustration to show you what he means:

Hugh then discusses attaching various associations to these purely imagined locations. These associations are generally Biblical in nature and in some cases surround a Memory Palace based on Noah’s Ark.

But Hugh did not expect you to visually imagine any of these locations. In the case of the Ark, he had a painting on the wall behind him to help illustrate the pairing of Biblical information with associations and conceptual spaces.

In other words, the answer is yes, you can combine Memory Palaces with any numerical mnemonic system including the Major System without visualizing anything in your mind.

How many Memory Palaces should I create if I don’t visualize?

Along with anyone else interested in serious results with these techniques, I suggest you assign as many Memory Palaces as you can.

That way, you’ll always be prepared to memorize anything you like without hesitation.

As two starter projects, I suggest you assign one Memory Palace for each letter of the alphabet.

Once done, learn the Major System and develop a 00-99 PAO. You can use this as a Memory Palace unto itself by experiencing the numbers in a field.

Or you can make the number-based Memory Palace Network more tangible by assigning it to a street (or series of streets) in a neighborhood you know reasonably well.

In other words, you snap your 00-99 figures onto the actual street addresses. Using my system, I would assign Nick Nolte to a building with the number 27 in the address because the Major tells us that 2 is N and 7 is K.

Can children or beginners learn to use Memory Palaces without visualization?

Yes.

That’s because the same conceptual rules are available to anyone at any age.

For examples of young people succeeding with the Memory Palace technique, please listen to my podcast episodes with Alicia Crosby and Imogen Aires. They were both just ten years of age when they were recorded.

Common to both success stories is parental involvement.

And that’s the key if you would like to see your kids succeed with these techniques.

Don’t just put a training guide in front of them. Learn the techniques yourself first so you can teach them from experience.

And share in the fun too.

Unlock the Power of Memory Without Relying on Images

From Simonides of Ceos and Thomas Aquinas to Bruno and beyond, the Memory Palace has never belonged exclusively to those who see vivid pictures in their minds.

The technique has always been grounded on multi-sensory and conceptual frameworks that turn raw data into lasting memories.

Whether you see high-definition images or nothing at all, you can build Memory Palaces that expand knowledge, sharpen focus and unlock your potential.

The key is to correctly understand your imagination and pair it with structure, practice and a willingness to experiment with the techniques.

If you’re ready to go deeper, register for my free memory improvement course:

It walks you step by step through mastering the Memory Palace.

Inside, you’ll get four concise training videos and worksheets designed to get you taking action immediately.

Last thought before we go:

The Memory Palace technique endures because vast amounts of people adapt it to their needs.

Whether by focusing on sight, sound, tactile sensations or pure thought, this technique reminds us that memory knows no bounds.

And all that mastering it requires is the same as anything else:

Constant study and practice.

In this case, that’s a wonderful requirement because using this particular learning technique is endlessly rewarding and fun.

Related Posts

- Memory Improvement Techniques For Kids

You're never too young to get started with memory techniques

- MMMPodcast Episode 001: 5 Ways To Ruin A Perfectly Good Memory Palace

In this session of the Magnetic Memory Method Podcast, I talk about the 5 ways…

- Obsidian & the Memory Palace Technique with Aidan Helfant

Aidan Helfant loves the Memory Palace technique, and he also uses Obsidian in some next…

8 Responses

Phenomenal post! So much to reflect upon and digest. Inspirational!!! Thank you.

Glad you found it so and thanks for letting me know!

I do aim to make these resources worthy of return and hope to hear any of your insights as you reflect to either add to this or built into a future post.

Thanks again and talk soon!

I continue to review the workshops & their correlating workbooks that I have attended. I am once again immersed in the The Memory Advantage 52 week Workbook (2nd time around). I continue in the MMM Master Program 3 years & counting. I am continuing to mnemonically and memory palace PAO Major System based, create scenarios involving my now 18 year old , freshman college student granddaughter, too! Thanks for continuing to facilitate this analog man in my senior learning years.

Always great to read about your progress, Bill, and fantastic that you’re still on the path with the Magnetic Memory Method Masterclass and its satellite programs.

I’m also always so inspired by how you’re helping your granddaughter. Thank you for being a person of outstanding service!

Anthony, do you have any good techniques to remember movies/episodes of tv/animes? I will start MMM soon.

Thanks for asking about this, Igor.

As a Film Studies professor I used MMM-style Memory Palaces to memorize the main hero’s journey, the Truby refinements and more technical material, such as the variations functions in Propp’s Morphology of the Folktale.

In other words, it’s not about different techniques, but understanding the narrative structures deeply. Then many stories memorize themselves through observation because you know all of their ingredients very well.

Additionally, this is how I wrote my Memory Detective novels. I drew upon this deep memorization of plot and narratology to build the plots and make the adventures satisfying while avoiding cliches.

Beyond that, I would suggest taking notes and practice identifying the story beats and conflicts, along with the emotional changes. Pretty much every scene has them, even anti-narrative series like Twin Peaks.

You probably don’t have to memorize them as such, but if you want to do so, the Memory Palace technique will serve without any additional technique. Except perhaps doing your own writing, which will sharpen your observation of various narrative structures.

My mother thought of this one: 52 cards in a standard deck of cards = the alphabet x 2.

Upon further reflection, I, myself, came up with this one:

A card for each letter of the alphabet, one uppercase one lowercase, such as could be used in the memorization of German nouns and other types of words in the German language.

This is great, Glenn, and compliments to both your mother and yourself.

I do have a deck of alphabet cards I use for drilling my mnemonic assocations. But I hadn’t though of splitting it between uppercase and lowercase.

One thing that’s brilliant about your idea is that it can work with a suggestion made by Giordano Bruno in some of his old memory training books.

He suggested that if you have to memorize capitalization, imagine your mnemonic figure standing. If you must know that a letter is lower-case, imagine that figure sitting.

None of this needs to be seen in the mind’s eye. You can think about it logically, conceptually, or just imagine feeling the difference. In fact, the difference between sitting and standing is richly tactile, lending even more power to those who use memory techniques without visualization.