There are more than a few ways to memorize a list.

There are more than a few ways to memorize a list.

But only one of them qualifies as the best.

The memory technique you’ll discover on this page will let you rapidly memorize any kind of list.

But not just for the short-term.

Due to the incredible nature of how this special technique works, you’ll also be able to retain any list of information you remember for the long term.

Ready to master this life-enhancing skill?

Let’s dive in!

How to Memorize a List Fast

There’s a fair amount of confusion about list memorization because there are different ways of doing it.

For example, if you’re a magician like Harry Lorayne, someone who popularized using mnemonics for remembering lists, you can use a simplified version of the pegword method for which he is famous.

But what if you want to memorize a list of numbers, like Akira Haraguchi who was able to commit 100,000 digits of pi to memory?

Perhaps you’re a medical professional who needs to memorize lists of symptoms, ph

Or perhaps you have more modest goals, such as memorizing vocabulary as part of learning a language. Or maybe you just want to remember a to-do list or the groceries you need to pick up from the store later.

For each of these goals, I suggest you sidestep most memory techniques and get started immediately with the Memory Palace technique.

Here’s how to use it.

Step One: Create Your First Memory Palace

In case you’re not familiar with this mnemonic device, here’s why this ancient memory technique is so useful any time you need to memorize a list of any kind of information. But first, let me tell you what it is.

A Memory Palace is a form of mental association where you place a list of information along a journey you assign within a familiar location. You’ve probably seen the technique used in Sherlock Holmes when the iconic character says, “I must go to my Mind Palace.”

If you were Sherlock and had to commit a list of facts about a case to memory, you would use your study and identify a few places (called loci) where you can “store” each part of your list.

For example, if you needed to remember the name of a suspect, you would place a mnemonic image on the chair labeled “1” in the illustration above. You do that by using a very special form of association, which we’ll discuss next.

Step Two: Pair Each Item on the List with an Association & the Memory Palace

When you’re memorizing a grocery list, you don’t necessarily need what mnemonists call mnemonic images. That’s because if you think about a giant carrot on the chair in your office, that’s weird and strange enough. You’ll probably automatically remember that carrot is the first item you wanted to buy.

But what if you have a list of facts or the names of the presidents? This kind of information needs to be transformed mentally into an association.

For practice, write out your to-do list. Let’s say you have to do something that’s kind of abstract at 2 p.m., such as attend a meeting about a technology with a challenging name. Like Microsoft’s Zune.

You will need to split this kind of word up a bit. Personally, I would think of both my favorite zoo in Berlin and Dune, the move. Zoo + Dune = Zune. An image of the Toronto Zoo crashing down on characters from Dune in a Memory Palace would make the name much easier to recall.

What about the time, 2 p.m.? For that you’ll want to develop skills with a number system, either the Major System or a PAO System. Although these forms of association are somewhat advanced, anyone can learn them.

Step Three: Gather the Information Into the Best Possible Order

Sometimes the order of items is clear.

However, when studying for an exam, you might need to rearrange the main points in different orders of importance.

For this reason, I like to extract information from textbooks onto flashcards. That way I can easily move the facts around and place them in the most logical order before creating associations and placing them in one of my Memory Palaces.

As a pro tip, here’s something you can try:

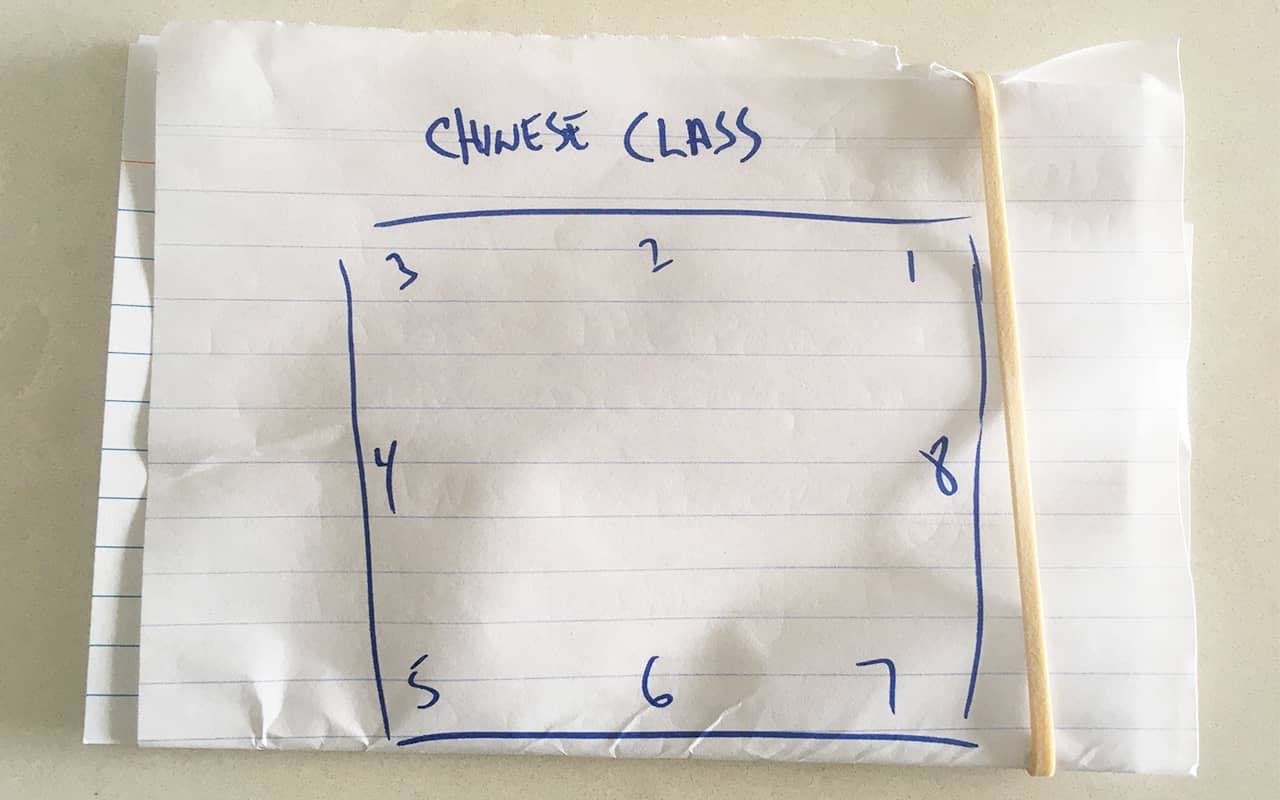

I normally draw my Memory Palaces out on a piece of paper (these drawings serve as essentially a list of already-remembered stations within a location).

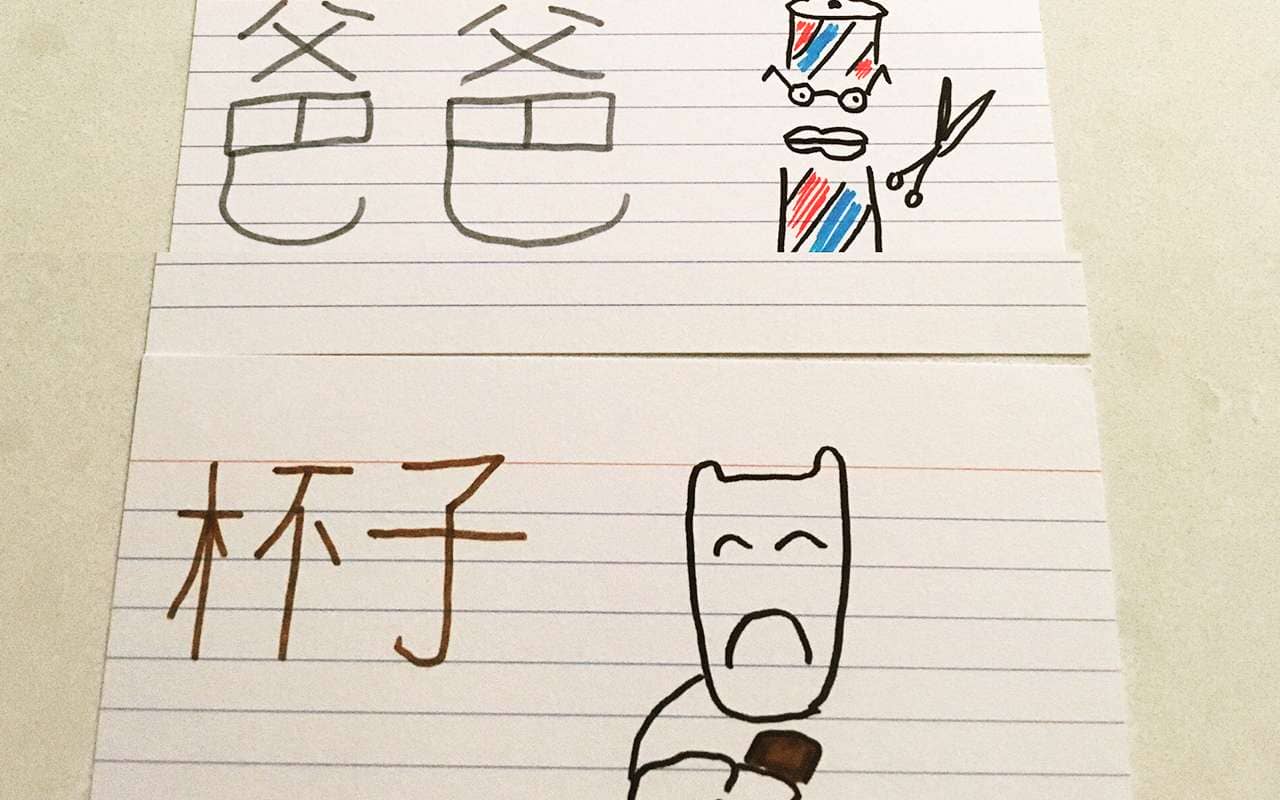

Then I fold the paper around the flashcards. The example you see above is one of the Memory Palaces I used when I learned Mandarin and passed Level III. Here’s what some of my cards looked like:

If you like the idea of being able to keep the lists of information you need to remember flexible, I also use special flashcard methods known as Zettelkasten and the Leitner System.

Step Four: Use Optimized Spaced Repetition For Revewing Your List

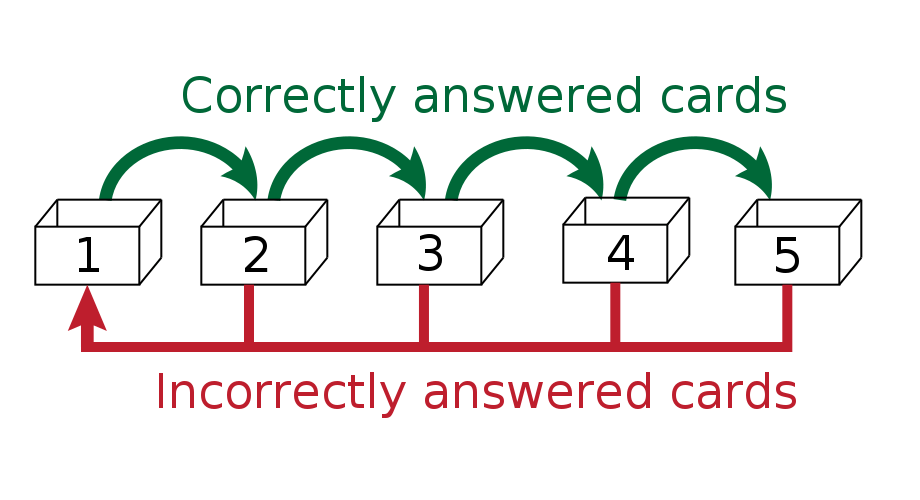

Here’s where the Memory Palace technique for memorizing lists really shines. Not only does the technique let you include as many items as you like. It also makes it easy to use what scientists call spaced repetition. If you’re using flashcards as I discussed above, this kind of rehearsal technique looks like this:

If you’re using the Memory Palace approach (which is kind of like using chairs and other furniture as index cards you draw on), here’s the process:

You simply mentally revisit the journey in your Memory Palace. On each station, you recall what funny image or direct association you put down. If I ask you to think about the list item we discussed on the chair in the Sherlock Mind Palace example above, you will probably remember that we talked about a giant carrot.

That one came easily.

But what about the item you needed to discuss at a technology meeting?

Although it may take a second, provided that you personalized your own mnemonic associations, you should be able to get back the word Zune.

And that’s another key:

As Robert Fludd used to stress about using these memory techniques, you need to personalize them so that when you are reviewing the images associated with the list items, they pop much better. He was completely right and contemporary science has shown this to be true. The principle of personalizing your images is now called active recall.

Many people learn this technique within minutes and immediately get it working.

But if you’d like more help, please register for my free course now right here:

It will help you create multiple Memory Palaces, discover fun and easy ways to use the method of association and more about how to rapidly apply spaced repetition.

Combined, you’ll soon have all the lists you want stored in long-term memory.

So what do you say?

Are you ready to give this approach to memorizing lists a try?

Make it happen!

Related Posts

- How To Renovate A Memory Palace (And When You Shouldn't)

If you've ever wondered how to make changes inside of a Memory Palace, this information…

- Method of Loci: 10 PRACTICAL Memory Palace Practice Tips

The loci method is easy to understand, but hard to practice consistently. These 9 PRACTICAL…

- What Is a Memory Palace? (How to Build and Use One Properly)

Discover the Memory Palace technique and why it’s still the most powerful memory method ever…