Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Robert Fludd is one of many people who taught memory techniques during the Renaissance.

Robert Fludd is one of many people who taught memory techniques during the Renaissance.

Although he’s largely forgotten due to some catastrophic errors in his thinking about medicine and science, his understanding of mnemonics is sound.

So if you’re not sure about where to start with Robert Fludd’s contribution to memory, you’re in the right place.

On this page, we’ll looking at his specific contributions to mnemonics for learning faster and remembering more.

Let’s get started!

Who Was Robert Fludd?

Robert Fludd lived during an era when it was possible to be considered an expert in multiple areas. He was born in 1574 and died 1637, and was the son of Sir Thomas Fludd, who served as Queen Elizabeth’s treasurer at one point.

Overall, his era was a time of explosive intellectual sharing through books and travel. But also one of controversy in which some people were forced into hiding for their ideas and even faced execution.

No stranger to controversy himself, Fludd studied successfully at St John’s College, Oxford, with a focus on medicine. He also traveled widely and other areas he studied and wrote about throughout his colorful life include:

- Astrology

- Math

- Cosmology

- Various religious philosophies

For our purposes, it is his role as a mnemonist that interests us the most. This is because one of his major works discussed the art of memory in greater detail than most books involving Memory Palaces of his era.

His key text has a very long title, both in English and Latin:

Utriusque Cosmi, Maioris scilicet et Minoris, metaphysica, physica, atque technica Historia (The metaphysical, physical, and technical history of the two worlds, namely the greater and the lesser)

Recently, just the mnemonic strategy portion of this book has been published by Lewis Masonic as Mnemonic Methods. I highly recommend reading it, especially since it comes with Fludd’s original Latin and illustrations.

Robert Fludd & the Philosophy Behind His Approach To Mnemonics

On the one hand, it’s easy to extract Fludd’s approach to memory techniques without talking about the historical figure at all.

He was largely passing forward what he’d learned from our ancient ancestors, after all. His description of the mnemonics stands the test of time because Fludd offered greater depth and more variety than others.

In my view, Fludd was also much clearer in technical matters (mnemotechnics) than his important Italian contemporaries Giordano Bruno and his student Alexander Dicsone. (Though as far as I’m concerned, Dicsone’s philosophy makes more sense and feels more aligned with truth as an emergent, nondual property in line with what our contemporary physics seems to be revealing.)

All in all, Fludd draws our attention to many technical points well worth focusing on – and he does so in a way that avoids the plagiarism in many other memory books, such as Matteo Ricci’s. And when it comes to what some people call the Roman Room technique, Fludd’s “theatre of the world” approach is well-worth close consideration. Because there’s one big part about it that I think many people have misunderstood that I’ll try to highlight for you below.

With all this in mind, here are some ideas that I feel are well worth highlighting from Fludd’s work. I’m confident they will assist you in your use of mnemonics if these finer points aren’t already on your radar and integrated in your practice.

One: Align Your Mnemonics As Close To The Target As Possible

People new to memory techniques often use vague and abstract mnemonic images.

Although this is not technically incorrect, it’s generally a poor approach. This is because the more vague and generic your images, the less likely they’ll help you recall what you’re trying to memorize.

Here’s what I mean:

Let’s say you’re memorizing a name like, well… Robert Fludd.

You could be forgiven for associating his name in a general way with the concept of flooding.

But Fludd would encourage you to go deeper by connecting the name to the flood of the Bible, ideally a specific painting of this scene you might know about.

Were he alive today and aware of the music producer Mark Ellis, who goes by the artistic name “Flood,” Robert Fludd would likely suggest you connect the idea of the Biblical flood using either linking or the story method with a specific painting and a known person who also uses a similar sounding or identical name as your core mnemonic strategy.

Two: Use Real Relationships

Sometimes you can’t find exact or near-exact associations like we’ve just seen in the Fludd/flood example.

In such cases, Fludd suggests that you focus on what he calls “real relationships.” For example, if you’re memorizing scripture, here’s Fludd in his own words:

If the second word is sword, then I can imagine this either by relationship, with Delilah moved to furious wrath breaking in two her husband’s scabbard… or by real action, with Delilah killing herself in despair.

Sounds extreme, right?

That’s Fludd’s point. If you can’t link sword with a sound-related figure like Jimmy Swaggart, then imagining the sword in an action already in your memory, you’ll do much better.

Three: Amplify The “Presence” Of The Imaginary

Fludd uses another term to describe mnemonic images you might find useful: real presence.

This tactic is important because you can’t always use real associations. Sometimes you have to imagine things like giant insects. To make them more present, you want your mental imagery to be as multisensory as possible.

A quick way to apply more sensations to mnemonics both real and imagined is to apply KAVE COGS:

- Kinesthetic

- Auditory

- Visual

- Emotion

- Conceptual

- Olfactory

- Gustatory

- Spatial

In other words, you’re rotating through a kind of Memory Wheel of possible associations.

But even in this case, Fludd suggests that you don’t stop at making imaginary images similar in sound to the core word. You need to elaborate them. True, some people with aphantasia report difficulties with this, but there are elaborative memory exercises that can help even people with the darkest of mental experiences.

Four: Use The Alphabet

The point comes through perhaps too subtly.

But Fludd does several times stress a point I’ve made many times about using the alphabet to help develop your mnemonic systems.

Fludd gives the example of using Neptune doing nothing to help you remember the concept of nothingness (a key point in his larger theory he shares with Bruno that I sometimes call the Chaos Memory Palace technique).

Fludd’s point is that if you have an “alphabetical sequence of the Gods,” you’ll always have highly specific mnemonic images you can use based on the spelling of the target information you want to learn. You just need to rotate through them, which is another aspect of the Memory Wheel principle.

Fludd gets even more specific by suggesting that when you want to memorize pronouns, you should specifically use monsters. Your milage may vary with heavily constrained mnemonic strategies by category, but you should know that I personally do not go quite so far.

For example, when I memorized the opening of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 59, to memorize “that” in the poem, I used Thor with a hat and switched to Thor pulling on his hair for “there.” I did not need to think specifically of what category Thor belongs to so I could match it with the grammatical function of these words in the sentence. (I was memorizing Shakespeare, after all, not learning grammar!)

But if the idea of hyper-categorizing your mnemonic associations helps you, give it a go and consult Fludd’s ideas on this for further details.

Five: Develop Image-Based Number Systems

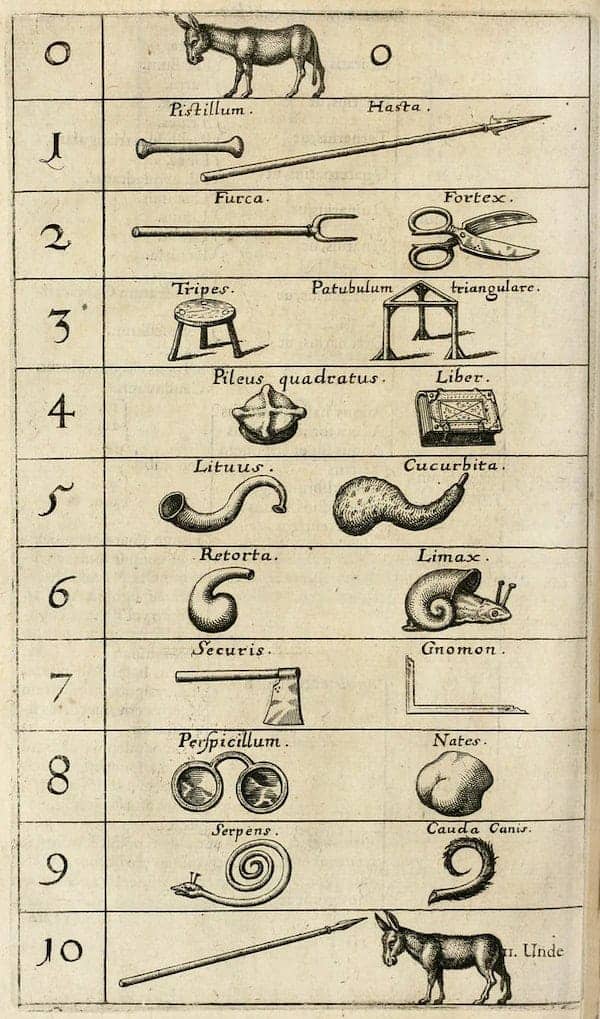

Although not his own idea, Fludd was one of the strongest Renaissance promoters of what we now call the Major System. It’s related to the PAO System and there are signs of this more evolved number mnemonic system in his work as well.

The core idea is that you develop images for each digit from 0-9. As much as possible, you follow the principle of the real he has already laid out earlier in Mnemonic Methods.

In other words, using a number-shape approach, his Renaissance-era pegword method suggests linking the number 6 with a snail shell shaped like a 6. I personally use a fishing hook for this, but any idea that works for you on a consistent basis is bound to be good.

In case it doesn’t leap out at you, in the image above, you can see the 00-99 PAO idea in Fludd’s work when he shows a spear with a donkey. The spear represents one and the donkey zero. The implication is that you would have two spears for eleven, a spear and scissors for twelve and so on.

Again, this is not quite the 00-99 system, but it’s a step in that direction and also presages Tony Buzan’s SEM3.

Six: Use Colored Memory Palaces

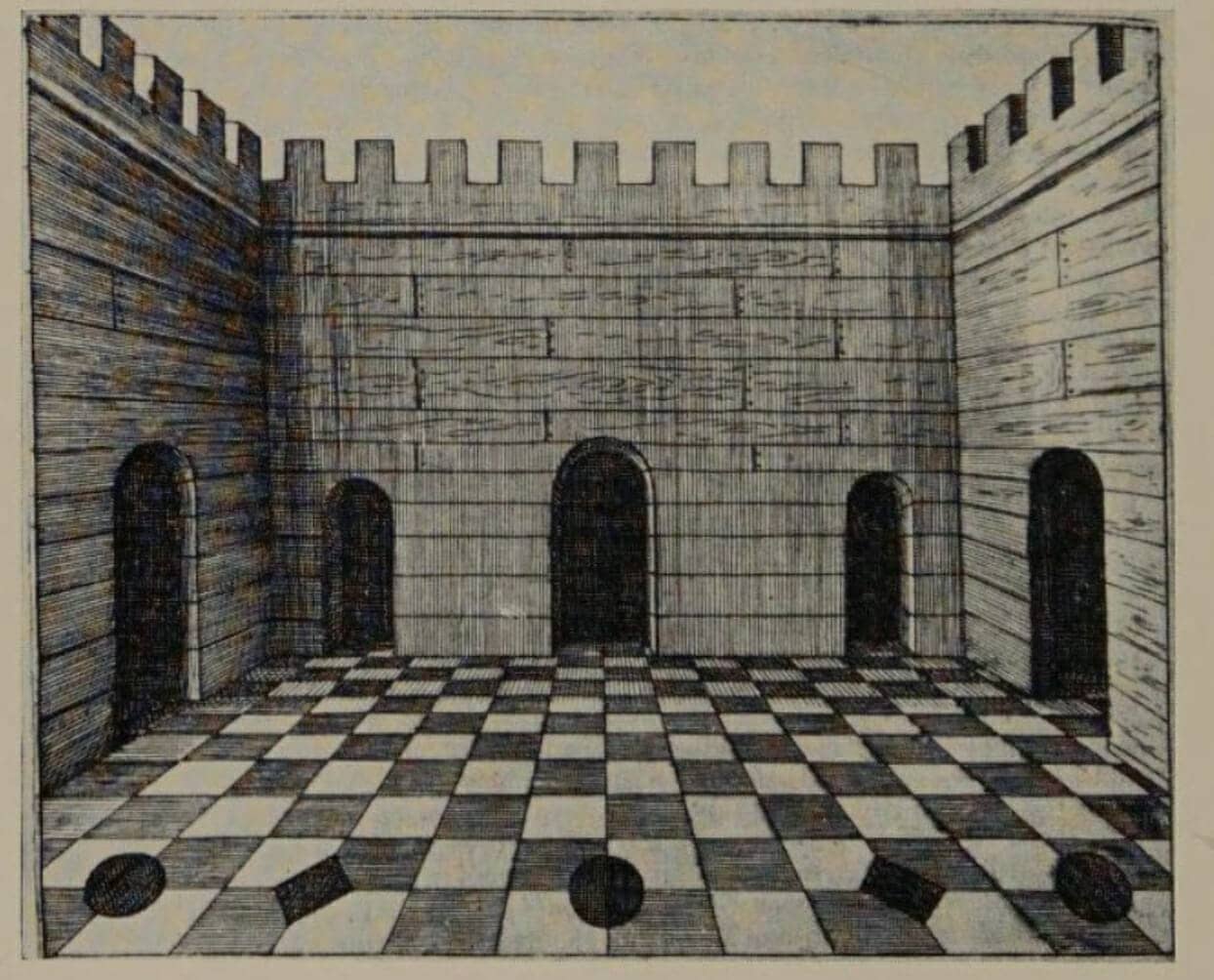

Fludd also discusses several unique ways to use Memory Palaces.

It’s not entirely clear to me what he means when he talks about colors. However, it is generally a common strategy to reuse Memory Palaces and avoid what memory enthusiasts call “ghosting” by either changing colors or applying substances.

For example, if you have three different versions of one Memory Palace, you would have one version be black, another blue and the final version red. Or, you could make a cloud version of the Memory Palace, followed by a fire version, a stone version, etc. Adding features like this will help make sure the information you store within the different versions of the same Memory Palace doesn’t blur together.

Fludd also suggests using different types of columns and geometrical floor patterns to help maximize the ways you use Memory Palace interiors.

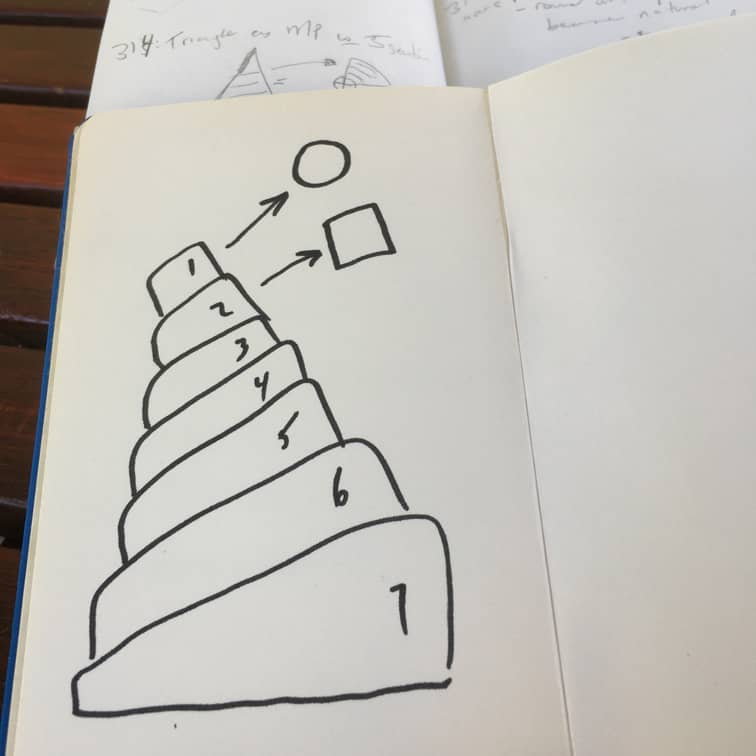

As Fludd is believed to have either drawn his own Memory Palace examples or participated in their creation, I have also drawn my own based on some of his suggestions.

I’ve experimented with these suggestions in a variety of ways. For example, in the drawing from my one of my Memory Journals above, I made a Memory Palace in which some stations were circles and others were squares. I used these as portals to specific kinds of Memory Palaces. (It didn’t accomplish much, but did make for a fascinating experiment.)

Overall, however, Fludd is clear about one thing. To avoid overwhelming yourself with unnecessary problems for most learning goals:

… you should choose real rooms… which are as different from one another as possible.

I have found this to be important in my own work, and here’s an important point. Many people think that Fludd’s theatre illustrations mean that he things you should create theatres out of thin air to use as Memory Palaces.

After reading Yates Theatre of the World for more information about Fludd and his time, I feel that Fludd probably had in mind that you would use real theatres. But more importantly, you would use the real actions and the real relationships as if they were playing out in the theatre of your mind.

Yes, the way he lays it out in his memory instructions is confusing. But I think this is the truth of the matter. Real Memory Palaces based on associations so “theatrically” strong, they cannot help but make you remember the target information. This approach will be much stronger than virtual or invented Memory Palaces for most of us.

Seven: Experiment

Although it can sometimes feel like Fludd overuses the word “should,” he also constantly encourages you to experiment.

In fact, success with the Memory Palace technique requires personal experimentation. Fludd doesn’t quite use these words, but I believe the meaning is the same.

As he puts it:

… memory can be strengthened in one of two ways: Either by the assiduous operation of the imaginative faculty, which inscribes in the memory impressions of actual objects and events through representations of fictitious ones, or through the power of medicines to restore a natural memory that has become unreliable.

He goes on to conclude that utter perfection tends to come through using your imagination. Pretty much the rest of the memory writing he offers focuses on how to experiment with your imagination using the guidelines he’s found most useful.

In many ways, Fludd holds up memory training with the same regard St. Aquinas did in terms of being good at both using the technique and letting it help guide the quality of your actions (prudence).

Should You Apply Fludd’s Memory Improvement Suggestions?

My answer is a resounding yes.

In fact, every idea that is good and true in Fludd’s memory writing is true because it’s true, not because he wrote about them.

Other ideas Fludd discussed haven’t stood the test of time. For example, Carl Shoonover shows in Portraits of the Mind that Fludd perpetrated ideas found in Galen, ostensibly because Fludd’s anatomy skills were lacking.

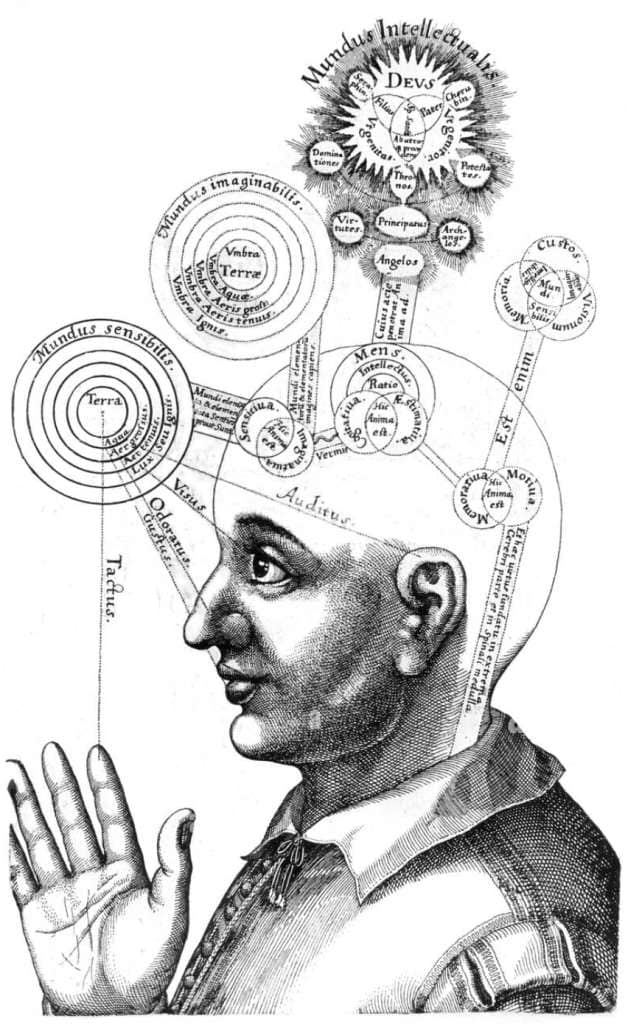

Fludd himself creates this impression by how he presented the optic nerve in one of his most famous illustrations.

As fantastic and beguiling as this illustration is, it has encouraged people to this day to perpetuate mystical ideas for which little or no evidence has been found.

Although I don’t think it’s a bad thing that copies of the Ars Notoria still circulate, Fludd says in Mnemonic Methods that some cases like angel-assisted learning are real.

Perhaps. And rest assured, I wish learning and life could be that easy.

But as William H. Huffman shows in his Robert Fludd and the End of the Renaissance, Fludd was likely an advocate for such pseudoscientific ideas because he belonged to Neoplatonic associations. He was trying to create a “theory of everything” not from the basis of a scientific standard that might have put more anatomical correctness into his illustration.

Rather, Fludd was more interested in maintaining what he called “my imitation of the Physical and Theo-philosophical Patron St. Luke… Eternal Word of Divine Wisdom.”

I have no doubt that some wisdom is better than others. But it is likely for the precise character of Fludd’s mysticism that his mnemonic contributions have fallen by the wayside compared to Bruno’s. But I still find them well worth going through and am glad Lewis Masonic has made them available in their excellent bilingual edition.

If you’d like to learn more about memory techniques like the Memory Palace in a way that combines the best of the ancient traditions with contemporary science and learnings from the memory competitors, feel free to sign up for my FREE Memory Improvement course now:

It will help clarify the scientifically valid tactics Fludd discussed through worksheets and video lessons.

My own philosophy is simple: Take action. Get results.

In the meantime, I hope these nuances from Robert Fludd’s work help you on your own use of memory techniques. He’s a lot of fun to read and when you take his fantastic illustrations into consideration with the fullest possible context of what his mnemonic instructions imply, they reveal much more than meets the eye.

Some of them can be used as Memory Palaces too, even if Fludd himself would not advise using them when there are so many rich and evocative locations in the world beneath your feet.

Related Posts

- The Memory Code: Prehistoric Memory Techniques You Can Use Now

Lynne Kelly, author of The Memory Code, shares her personal experiences learning ancient memory techniques…

- 2019 Canadian Memory Champion Reveals His Memory Secrets

James Gerwing completed the Magnetic Memory Method Masterclass a while ago. In 2019, he became…

- Surviving PTSD With The Help of Memory Techniques Featuring Nicholas Castle

Nicholas Castle used memory training and memory techniques to help heal his PTSD. Listen to…