Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Is St. Augustine’s memory philosophy practical? Or is it just intellectual noodling from yet another philosopher of times past?

Is St. Augustine’s memory philosophy practical? Or is it just intellectual noodling from yet another philosopher of times past?

If you’re interested in St. Augustine’s comments on memory, but aren’t sure exactly what he was going on about, you can rest assured of one thing.

What he had to say about memory is more than just interesting. And it’s not intellectual noodling. Far from it.

Even where Augustine’s philosophy of memory does not gel with contemporary science, it’s astonishing how close some of this thinking gets to what we now believe is true about memory.

Plus, thinking through his ideas is itself a good memory and critical thinking exercise. It’s worth learning about just for the mental workout.

Straight up: a fit mind will always be able to learn faster than a flabby one.

The best part?

Once you understand St. Augustine on memory better, you’ll make better learning choices too.

Sound good?

Let’s dive in!

Who Was St. Augustine?

Augustine of Hippo lived from 354 AD to 430 AD. He is remembered for essentially inventing the autobiography and auto-hagiography by writing his Confessions.

This literary offering is quite unique because, as Andrea Nightingale points out, a substantial part of how and why he was made a saint comes from things he said about himself.

Not only that, but Augustine helped shape how we interpret texts, a process known as exegesis. Because he focused so much on his own memory and memory at large in his works, he has shaped how many cultures have come to interpret the experience of having a self.

We’ll get more into why this contribution is so important in a moment, noting that Augustine also explored many other issues. For example, he discussed the nature of evil, desire and the philosophical ideas of Plato.

He wrote prolifically, and his City of God is not only studied as a book of Christian philosophy. It was a key part of my political science program when I was an undergrad. It is a very good text to compare and contrast with Plato’s Republic, for example.

Augustine was also deeply interested in the liberal arts and the memory and persuasion skills discussed in Rhetorica ad Herennium. He held critical thinking to be very important and demonstrated several ways to do it in his works.

What Was St. Augustine’s Philosophy of the Mind & Memory?

Augustine has been influential on people who use memory techniques. In fact, it’s possible that the term Memory Palace comes from his oft-quoted line:

And I come to the fields and spacious palaces of my memory, where are the treasures of innumerable images, brought into it from things of all sorts perceived by the senses.

But when it comes to mnemonics, Augustine’s philosophy of memory is useful more in a roundabout way. As I share with you the main points I’ve picked up from reading him, we’ll patch those valuable angles in.

One: Augustine Helps You Meditate On The Nature Of Data

Because examples of autobiography prior to Augustine are hard to find, he didn’t have many models to copy. Paula Fredriksen suggests that Augustine probably had the Pauline Epistles. These books of the Bible are letters and certainly have an element of reflective thinking related to autobiography.

But Augustine isn’t just writing about himself. He’s thinking deeply about the nature of his memory and how it allows him to consider facts about his own experience. To use modern terms, he’s essentially thinking about how the mind collects data and transforms it into a useful form.

We now call data we have gathered for analytical thinking, “information.” The next step he considers is how that information becomes knowledge and ultimately wisdom.

These aren’t merely philosophical questions. They are questions of epistemology – the art and science of how we know something is true or false.

Two: Memory Helps Us Create & Experience Meaning

Augustine notes a few interesting paradoxes as he reflects on the nature of his personal experience of memory.

For example, he observes that he can remember a time when he felt joyful, yet do so in a completely neutral state. It’s really weird if you think about this and experiment with thinking through happy memories in a neutral way yourself.

This mental exercise suggests that there may be a difference between information and sensation.

At some level, he thinks there has to be a difference. This is because in order to trust others, we can’t let ourselves get caught up in superstition. We have to analyze them rationally and sometimes let go of previous bad memories we might have about another person or group.

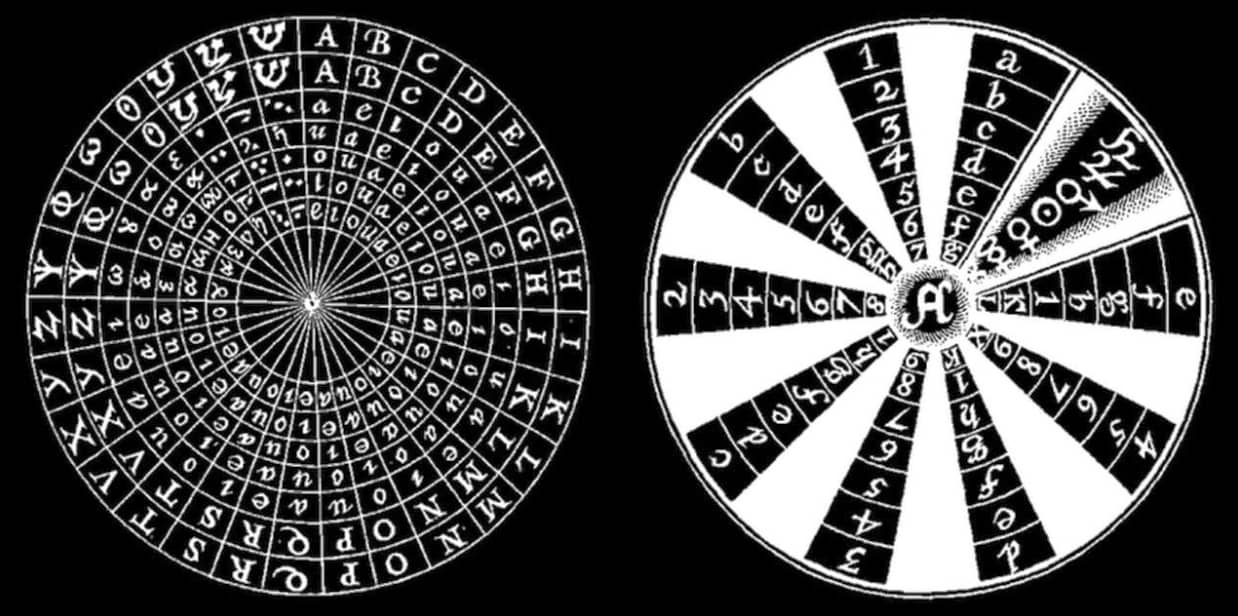

Part of our memory allows for rational and logical thinking. We can use our memory to sort, sift and screen a variety of sensations (data). We then use our minds to make them meaningful, specifically through the application of categories. I believe Augustine’s reflections on categorical thinking probably influenced Ramon Llull’s development of the Memory Wheel.

To take things one step further, Augustine seems to suggest that we use our memory to make memory itself meaningful to us. As he writes in the Confessions:

The interior sense perceives not only the things referred to it by the five senses, but also the sensations themselves.

Then later:

[Memory] is a faculty of my self and belongs to my nature. In fact, I cannot totally grasp all that I am. The mind is not large enough to contain itself… When I remember memory, my memory is present to itself by itself. Nothing is so much in the memory as memory itself.

What I believe Augustine is suggesting here is that memory is itself a sensation. Only by reflecting on it thoroughly and deeply can memory truly become as fully meaningful as many of the great memory masters throughout history have proclaimed it to be. I’m talking about people like Giordano Bruno, St. Thomas Aquinas, Matteo Ricci, Aristotle, Albertus Magnus and many more.

Three: Coping With Meaninglessness

As a religious thinker, Augustine concludes that there’s an infinite number of data points about God and about ourselves. No matter how much your memory comes to contain in those “spacious palaces” of memory, knowledge will always be incomplete.

In some ways, I think he’s anticipating Gödel’s Incompleteness Theory, but his notion of mental imagery seems to allow for a sense of totality even if you can’t understand everything. This is quite different from Giordano Bruno’s “Chaos Memory Palace” theory which suggests that you actually can understand it all.

But he shares with Bruno the idea that memory is not like a sponge. When you learn something new, you don’t have to forget what you already know. As he puts it, new information “displaces no volume.”

How did I recognise [things I did not know] and say, ‘Yes, that is true’? The answer must be that they were already in my memory, but remote and pushed back… as in in most secret caverns.

It’s a feel-good idea. It allows for a philosophy in which humans are made in the image of a creator. Memory becomes a tool that allows the seeker to find God through a process of inquiry into memory:

O lovely light… I shall pass beyond memory to find you: but where will I find you? If I find you beyond my memory, then I shall be without memory of you. And how will I find you if I am without memory of you?

Augustine’s answer is that the “memory” of god is built-into the system. But these days many of us recognize a more Darwinistic impulse towards belief as a survival strategy in the face of a universe in which life is the exception to the rule, with no empirical demonstration of a reason why anything should exist.

For a strong alternative in an another important realm of philosophy to Augustine’s a priori-style of thinking about memory, see Nietzsche’s “rumination” on memory, especially in Human, All Too Human.

Four: Memory For Critical Thinking

I just used the word “rumination.” That’s because Augustine sees memory as something like the series of stomachs you see in cows. It’s not just that memory is “the stomach of the mind,” but that it digests different kinds of thoughts at different rates of speed.

Some of those thoughts relate to categories Augustine picks up from Stoicism. He focuses particularly on these 4 “perturbationes”:

- Fear

- Desire

- Joy

- Sadness

These are categories we can think through when trying to understand memories that arise through autobiographical memory processes. Or we can use these specific categories when thinking about prospective memory – such as our memory of what we need to do in the future. This would include thinking through what sometimes holds us back from taking action on those things we need to get done.

Again, I believe Augustine’s thinking here was almost certainly influential on tools developed later like the Memory Wheel and ars combinatoria. You can also think of taking time to focus on your issues by using four simple categories like this as a form of chunking.

Long story short, Augustine seems preternaturally aware that short term memory (or working memory) operates more efficiently when dealing with smaller units of information. Less is truly more.

Five: Memory Is About Ability

Although Augustine goes to great lengths to show that memory is essentially spiritual, he’s ultimately very practical. He sees memory as something that can be astonishingly easy for some things, like remembering the colors and the days of the week. Part of this effect St. Augustine notes is coming from something we call context dependent memory, but also the sheer amount of spaced repetition we get from this kind of quotidian information.

In other cases, memory can be much more difficult, especially when learning complex topics. Although Augustine doesn’t have a very good answer when he suggests that all of this understanding is already in your mind and just needs to be uncovered, here’s his most practical tip:

He says that your ability to remember and understand ultimately shapes your ability to succeed. You have to be able to demonstrate an understanding because you need to judge your own passions to avoid bad behaviours and the negative outcomes they create.

The experience of joy, he tells us, essentially comes from studying and understanding the information that helps you guide your actions towards joy. Doing this will in turn provide you with better mnemonic images as you practice the art of memory. It’s a self-reinforcing system in that regard, and that’s why linking your learning choices and memory abilities wisely will ultimately help you learn faster.

Yes, you can remember physical things like rocks and houses and the names of the foods you like to eat. But to really get ahead, you need to also be able to work with non-existent things. Like numbers and the concepts related to the liberal arts. Or the ideas in the best books about philosophy you come across over your lifespan.

In my view, he places a premium on abstract thinking over concrete thinking. I think this emphasis is as wise now as it surely was then.

This is so important because Augustine understands the nature of information the same way Bruno did, Galileo did and I do. It’s infinite, unfolding in time and as Augustine says of interpreting scripture, “not one line is exhaustible.”

And to deal with it, St. Augustine tells you something every memory expert worth their salt admits. His memory is not perfect. Far from it.

Not only that, Augustine uses mnemonics with passion because he observes that God himself uses them. Just take a look at Genesis 9:13-15 if you don’t believe me:

I have set my bow in the cloud, and it shall be for a sign of the covenant between me and the earth. And it shall come to pass, when I bring clouds over the earth, and the bow is seen in the cloud, that I will remember my covenant.

If putting a rainbow against the backdrop of the sky as a reminder isn’t the Memory Palace technique writ large, I don’t know what is. No wonder Eran Katz called his book on mnemonics, Where Did Noah Park the Ark?

Augustine On Memory Is Worth Your Time

Today’s summary is really just scratching the surface. There’s much more you’ll glean from reading St. Augustine on memory yourself.

My goal has been to show you how Augustine’s observations about memory land on many of the features scientists have confirmed and named in our era.

But St. Augustine didn’t need spreadsheets and graphs to know just how valuable using memory itself as a kind of concentration meditation can be.

He knew intuitively and by applying logic that memory really is like a room:

…a spreading limitless room within me.

And if that’s an experience you’d like to enjoy yourself, then follow his advice to focus on learning the skills that lead to joy. Get my FREE Memory Improvement Kit now:

It will take you deep into everything you need to know about the Memory Palace technique.

Before you know it, you will know as Augustine did that memory is where you are most yourself, so long as you can come to truly perceive memory for what it is:

A sensation that senses all the other sensations.

“Who can reach memory’s utmost depth?” Augustine asks.

The answer is you, so take a deep dive inside by learning memory techniques and applying them to the information that matters. Your joy is guaranteed when you do.

Related Posts

- How to Use Superheroes In A Memory Palace To Learn Faster

If you know Batman, you can use him to help you memorize foreign language vocabulary…

- 5 Memorization Techniques That Help You Learn Faster

Memorization techniques can be confusing because there are so many. Knowing these 5 benefits will…

- Memory Athlete Braden Adams On The Benefits Of Memory Competition

Braden Adams is one of the most impressive memory athletes of recent times. Learn to…