Ever stepped into a store and realized you’ve forgotten what to buy?

Ever stepped into a store and realized you’ve forgotten what to buy?

It’s a clue that your working memory isn’t holding on to information long enough for you to use it!

Working memory is like your mental sticky notes. Sometimes, it doesn’t stick!

So, how does it work? Does it weaken with age? And can you improve your working memory?

In this article, I’ll dive into every detail you need to know about working memory, how it works, and much more. I’ll also show you three easy ways to boost your brain power so your working memory is always at its sharpest.

Here’s what I’ll cover:

-

- What is Working Memory?

- Examples of Working Memory

- A Brief History of Working Memory

- Theories of Working Memory

- Working Memory Capacity

- How Does Your Working Memory Develop Over Time?

- Neural Mechanisms of Maintaining Information in Your Brain

- Does Genetics Influence Your Working Memory?

- Does a Better Working Memory Mean Better Academic Achievement?

- Relationship Between Working Memory and Attention

- How is Working Memory Connected to Neural Disorders and Brain Injuries?

- How Do Kids Use Working Memory?

- How to Find Out if Children (or Others) Have Working Memory Issues

- Can You Sharpen Your Working Memory through Training?

- 3 Ways to Improve Your Working Memory

What is Working Memory?

Your cognitive system that can hold a limited amount of information temporarily is called working memory.

Working memory helps you in reasoning, making decisions, and guides your behavior in any situation.

Imagine a science class where the teacher is talking about planets. His students may put pieces of information in some order.

For example, they might picture Mars and Jupiter’s discovery on a timeline. They may also categorize what they hear — for instance, Uranus and Neptune as “blue planets,” and so on.

Some people use short-term memory and working memory synonymously. But there’s a key difference between the two.

How is working memory different from short-term memory?

Short-term memory is your ability to remember information over a short period, say, a few seconds. It can only hold information, while working memory can manipulate this information.

Working memory involves both retaining and processing the information.

How is it different from long-term memory?

Your long-term memory holds information durably and has a larger storage capacity. It may constitute past events, semantics, learned knowledge, how to use objects, motor skills, and much more.

Working memory acts like a gateway to long-term memory.

Working memory skills are associated with a temporary activation of your neuron network, while long-term memory is connected to physical neuronal changes. That’s why your working memory is more susceptible to shocks and interruptions.

Examples of Working Memory

You’re using your working memory when you:

- Prepare ingredients to cook a dish while watching the recipe video on TV

- Remember what the teacher taught in class to make notes soon after the class ends

- Make a mental calculation of your total bill while buying groceries in the supermarket

Working memory is complex — and you can’t understand it well without going through its history and the studies conducted by researchers over the years.

A Brief History of Working Memory

The term “working memory” was introduced in 1960 by cognitive psychology researchers George Miller, Eugene Galanter, and Karl Pribram.

In 1968, Atkinson and Shiffrin proposed a multi-store model suggesting that human memory is made up of:

- A sensory register

- A short-term store (working memory or short-term memory), and

- A long-term store (long-term memory).

Over 100 years ago, Hitzig and Ferrier described that the frontal cortex is primarily concerned with intellectual and attentional functions rather than sensory and motor ones.

Theories of Working Memory

Many theories have explained the anatomical and cognitive aspects of working memory.

Let’s examine the most important ones.

The multicomponent model

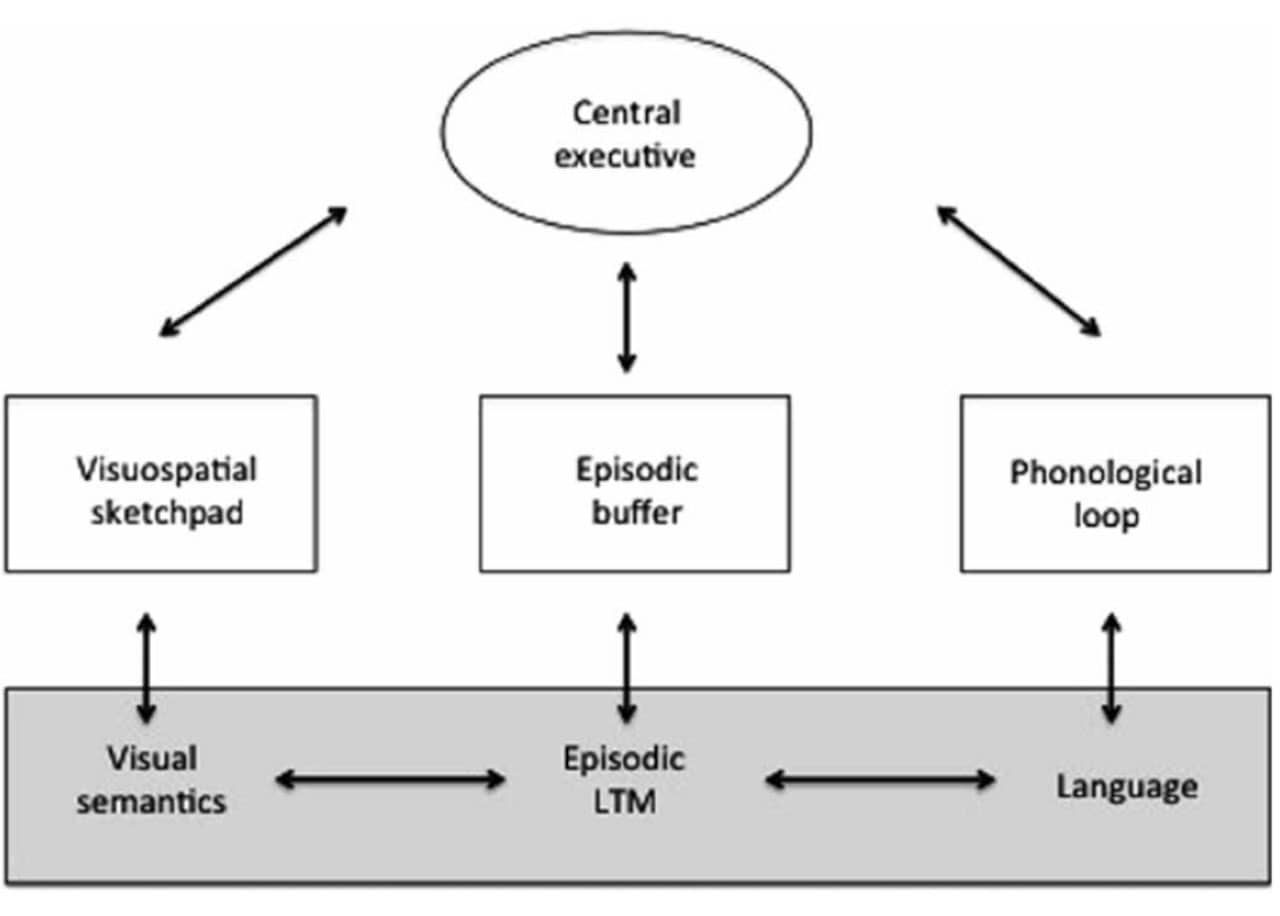

Alan Baddeley and Graham Hitch proposed that working memory doesn’t hold information in one store. Instead, different kinds of information are stored in different systems.

Central executive: This versatile component drives the whole system by directing attention and prioritizing activities. It controls attentional processes and doesn’t store information.

The central executive acts like a control center, directing information between the phonological loop and the visuospatial sketchpad. (More on this later.)

Phonological loop: The phonological loop component deals with written and spoken information. The phonological loop manipulates speech-based information.

It is further divided into:

- Phonological Store that processes speech and stores words, and

- Articulatory Control process that processes speech, and rehearses and stores verbal information.

Visuospatial sketchpad: This is the component that stores and processes information in a visual and spatial manner.

You can apply working memory directly to any daily task — for example, reading (phonological loop), problem-solving (central executive), and navigation (visuospatial processing).

In 2000, Baddeley extended this working memory model with another component — the episodic buffer. It is a link between working memory and long-term memory.

An embedded-processes model of working memory

According to Anders Ericsson and Walter Kintsch, long-term working memory is made up of retrieval structures that seamlessly retrieve information for any daily task.

In 2010, Cowan suggested that working memory representations are a subset of representations in long-term memory.

Do you know your working memory capacity?

Working Memory Capacity

Working memory has a limited capacity.

In 1956, Miller claimed that the short-term memory capacity limit is around seven chunks or seven elements. These elements could be letters, words, digits, or any other unit.

But later research partially disproved this, saying that the information processing capacity limit depends on the kind of unit.

How is working memory capacity measured?

Working memory capacity can be measured through dual task paradigm tests that require you to commit a short list of items to memory while doing some other task.

If you recall five items, your working memory capacity is five. This is a memory span measure and is also called working memory span.

Daneman and Carpenter invented the reading span test wherein you read a paragraph and recall the last word of each sentence you read.

It was later proven that working memory capacity could be measured with a short-term memory task with no other processing component.

Also, working memory capacity measures are related to your performance in a complex cognitive task like reading comprehension, problem-solving, reasoning, and IQ.

Studies on working memory capacity

There are many hypotheses on the nature of memory capacity.

Decay theories

The time-based resource sharing theory assumes that the contents of working memory decay over time unless you rehearse it many times. Also, you need focused attention if you perform a processing task concurrently.

The amount you forget depends on how much attention, “cognitive load” or working memory load you need to give to the processing task. This, in turn, depends on how quickly you need to do the task and how many steps it takes.

Resource theories and Interference theories

According to resource theories, the capacity of working memory is shared between all representations in working memory at the same time.

Some scientists proposed that newer information replaces the old in working memory.

For example, if you’re trying to do a serial recall of 10 words in order, the second or third words may pop into your mind as you recall the first. In other words, they compete for retrieval.

Next, did you know that working memory is sensitive to aging?

How Does Your Working Memory Develop Over Time?

The performance of working memory has been found to increase from infancy, through childhood and teenage years into adulthood — thanks to the normal development and degradation of your prefrontal cortex (PFC) in the frontal lobe of the brain.

During childhood, the capacity of working memory is a strong indicator of cognitive function development. It can even predict the future reasoning abilities of children.

The slower processing ability during old age allows more time for the contents of working memory to decay. This can reduce your working memory ability.

Also, Robert West argued that working memory depends primarily on the prefrontal cortex, which deteriorates more than other parts of the brain as you grow old.

So, how does working memory work?

Neural Mechanisms of Maintaining Information in Your Brain

A brief look at the various research efforts in this area will help to understand this better.

In their 1930 study on monkeys, Jacobsen and Fulton showed that spatial working memory performance was impaired by prefrontal cortex lesions.

Goldman-Rakic described the circuity of the prefrontal cortex and its connection to working memory. This made it easier for scientists to understand the neurological basis of higher cognitive ability, as well as disorders like ADHD.

Localization in the brain

The localization of brain functions is the idea that the brain is made up of specialized parts, each with a specific function.

Studies using brain imaging methods like PET and fMRI showed that a working memory function activates the PFC and other parts of the cortex. A spatial task uses more of the right hemisphere, while verbal and object working memory uses more left-hemisphere parts.

A working memory task (WM task) uses a network of PFC and parietal areas, often connecting both these areas during the task.

Studies like the prefrontal cortex basal ganglia working memory model have proven that the PFC works with the basal ganglia to accomplish a working memory task.

Do stress and alcohol affect working memory?

Short answer: yes.

Studies conducted by Arnsten and others show that working memory is impaired by chronic and acute psychological stress. This happens because stress releases catecholamine in the PFC, rapidly decreasing neuron firing.

Exposure to chronic stress can even change the architecture of the PFC, causing dendritic atrophy and spine loss.

Alcohol abuse can lead to brain damage, impairing working memory. Alcohol affects the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) response. Young and older adults dependent on alcohol show weaker performance in working memory tasks, particularly visual working memory.

Do Genetics Influence Your Working Memory?

Working memory capacity is heritable to a certain extent. One’s genes partially influence the individual difference in working memory.

Some studies have shown that the brain-expressed gene LRFN2 has a role to play in learning disability, specifically for working memory processes and executive function.

The ROBO1 is also considered to play a part in the phonological loop component of working memory.

However, there is no clear consensus on which genes affect the functioning of working memory.

Does a Better Working Memory Mean Better Academic Achievement?

Working memory capacity (WMC) is important for many cognitive processes, including solving mathematical and creative problems.

In 1980, Daneman and Carpenter noted a correlation between working memory capacity and reading comprehension.

Later, Beebe-Frankenberger and Swanson found they could predict the performance of primary school students in math problem-solving using students’ working memory performance.

Impaired working memory can affect reasoning and learning outcomes adversely. It’s a high-risk factor for educational underachievement for children.

The Relationship between Working Memory and Attention

Attention and working memory aren’t the same, but they’re closely linked. And both are key to learning and reasoning.

Attention allows you to focus on information-processing relevant to your goals, and ignore distractions.

At the same time, working memory helps you encode information, manipulating it to make sense to you.

Kids with ADHD, executive function problems, language-based learning issues, and any other learning disability struggle with working memory and attention.

How is Working Memory Connected to Neural Disorders and Brain Injuries?

Several neural disorders are accompanied by poor working memory.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Early signs of ADHD arise from a working memory deficit or a general weakness in executive control. People who have ADHD are noted to fare lower in spatial and verbal working memory tasks, and in many other executive function tasks.

Some children with ADHD may have high or average IQ scores, just like gifted children, yet they struggle with learning. This is because students with ADHD have a weak working memory, which results in poor grades.

Alzheimer’s Disease

People with Alzheimer’s disease suffer from a working memory deficit mainly due to errors in feature binding.

Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s Disease results in diminishing verbal working memory. People with Parkinson’s Disease do not have misbinding issues. They have working memory difficulties, but they are associated with making random errors.

Huntington’s Disease

People with Huntington’s Disease have various cognitive deficits, including significant difficulties in working memory.

Traumatic brain injuries

Traumatic brain injuries cause synaptic and intrinsic changes in the prefrontal circuit. People with traumatic brain injuries were found to show weaker verbal short-term memory and verbal and visuospatial working memory than others.

It’s also interesting to observe how children, in particular, use their working memory.

How Do Kids Use Working Memory?

Kids use working memory to access information, remember instructions, pay attention, learn to read, and to learn math.

When a teacher reads out a math problem, students need to remember the numbers, figure out which formula to use, and solve it.

Kids who have weak working memory skills struggle to grasp the problem and solve it at the same time. In a language class, such children may find it difficult to remember the sentence that needs to be written down and remember spellings simultaneously.

Having a weak working memory will lead to learning and reasoning difficulties.

If your child has working memory problems, you need to identify these issues before they can be solved.

How to Find Out if Children (or Others) Have Working Memory Issues

First, you need to determine if your child or relative has poor working memory skills or an attentional problem.

Here’s how you can investigate:

- Do a complete evaluation

- If working memory problems are found, you should check for other problems related to executive functions like ADHD. If ADHD is detected, you can proceed with specific treatments for that disorder.

- You can also work with your child’s school to find solutions like writing brief notes to remember important pieces of information.

And this isn’t an easy process!

Wouldn’t it be better if you could train your brain to improve your working memory?

Can You Sharpen Your Working Memory Through Training?

Let’s look into some key research findings to answer this.

In his study, Torkel Klingberg showed that you could improve working memory in ADHD patients through working memory training using his CogMed computerized programs. However, it was later proven that these programs have only a negligible effect on intelligence and attention.

In another study, working memory training was shown to improve fluid intelligence in healthy young adults.

A 2005 study also found that training working memory can improve the performance of children with ADHD and other specific conditions.

Although there’s no consensus on whether you can improve working memory capacity significantly through training, scientists agree that you can train your brain to use working memory resources better.

The most effective option is to keep your memory sharp over the years by training your brain to retain information and be able to recall it at will.

Let’s look at three easy ways to sharpen your memory power.

3 Ways to Improve Your Working Memory

Playing brain games on smartphone apps may sound like the easiest way to improve your memory. But games may not stimulate your brain effectively.

These types of mental exercises do actually work if you incorporate them into your daily routine.

1. Build Memory Palaces

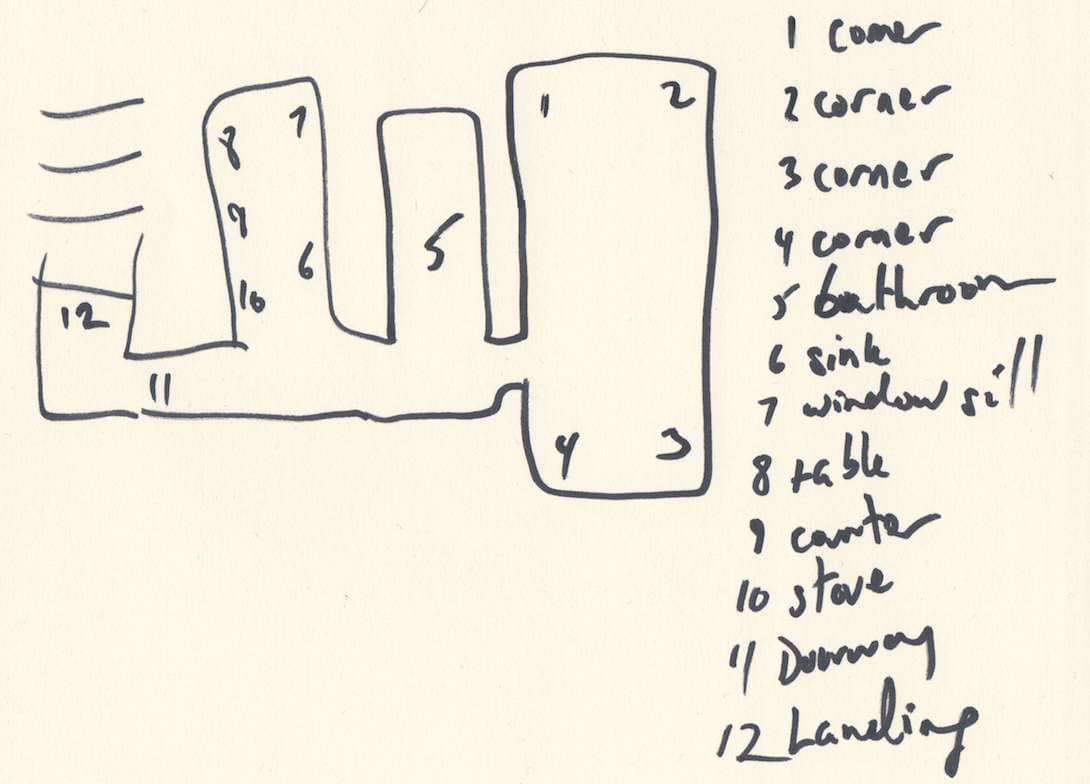

Building Memory Palaces using the Magnetic Memory Method is an incredible technique that will help you boost your working memory and long-term memory.

Creating Memory Palaces draws upon your visual working memory, spatial memory, episodic memory, semantic memory, procedural memory, and autobiographical memory.

This helps you move information from your working memory to your long-term memory faster, and with more reliable permanence.

For example, try this when learning a new language: mentally walk around your home and use associations to place words related to shopping on your dining table, words related to food on your sofa, and so on.

By doing that, you access visual memory cues that are blueprinted in your mind without you being aware of it.

Creating Memory Palaces lets you exercise your ability to recall huge amounts of detail with visual memory. Use it to learn the most important parts of an entire textbook, a new language, or a new instrument.

Once you master it, you can create as many Memory Palaces as you want to retain and recall information whenever you want.

2. Try Meditation

Mindfulness meditation has shown promise in improving our working memory.

Meditation helps you concentrate or focus your attention on what’s important to you. This is due to increased gray matter density in some parts of your brain, better control of brainwaves, and better white-matter connectivity.

So make it a point to practice any form of mindfulness meditation for at least 15 minutes a day.

3. Get Enough Sleep

Several studies have shown that sleep deprivation inhibits mnemonic abilities, executive function, and attention. It increases response times and makes you more error-prone while doing simple tasks.

It influences neural activation in the frontal and parietal cortices — both of which are areas critical for working memory.

It’s important that you get at least 7-8 hours of sleep at night to recharge your brain cells and maintain optimal working memory performance.

A Magnetic Method to Improve Your Working Memory

Once you get your working memory on track, you won’t have to carry paper lists next time you go grocery shopping. Neither will you struggle to remember an address while listening to instructions on how to get there!

Incorporating these three easy techniques, especially creating Memory Palaces, into your daily routine will give your memory a big boost.

Want to learn more about how Memory Palaces work? Get started with the Magnetic Memory Method Masterclass!

Related Posts

- Memory Athlete Braden Adams On The Benefits Of Memory Competition

Braden Adams is one of the most impressive memory athletes of recent times. Learn to…

- 3 Blazing Fast Ways To Increase Memory Retention

Memory retention... what the heck is it? Is it worth worrying about? If so, can…

- Luca Lampariello On Working Memory And The Oceans Of Language

Listen now to this second MMMP interview with world-renowned polyglot, Luca Lampariello.