Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The Roman Room method is just one term for the most powerful memory technique humanity has ever known.

The Roman Room method is just one term for the most powerful memory technique humanity has ever known.

It helps you memorize information for a few simple reasons we’ll explore on this page.

The best part?

The Roman Room technique helps you memorize information quickly.

What kinds of information?

Everything from foreign language vocabulary to entire speeches.

Ready to learn and master this powerful learning technique?

Here’s a Table of Contents for you of what’s on this page for you:

The Origin of the Term Roman Room?

Roman Rooms or Memory Theatres: Which Is Better?

How To Prepare To Use A Roman Room

How to Use Your First Roman Room

Practicing the Roman Room Method

How to Expand Your Roman Rooms

How to Modify A Roman Room

Is the Roman Room Method the Best Memory Technique?

The Origin of The Term “Roman Room”

First off, it’s important to repeat that this term is just one variation of a mental tool that appeared many thousands of years ago, long before Rome was even built. The term “Roman Room” means practically the same thing as:

- Journey Method

- Memory Palace

- Mind Palace

- Memory Castle

- Memory Room

- Method of Loci

I’ll never forget one of my first students – he was 88 and didn’t like any of these terms. So I said call the Roman Room technique whatever you like. He chose “apartments with compartments.” Once settled, he went on to revive his German and memorize dozens of poems.

But there’s a reason some people call this technique the “Roman Room.” This is because Roman Orators used their homes, and even the stages they spoke from, to help them memorize and recite their speeches.

In fact, a phrase we still use today is thought to come from the use of rooms as memory devices. When a speaker would say, “In the first place” or “in the second place,” this verbal habit was referring to the information in a mental room used to store the point. It’s entirely possible that the people in the audience also used the technique, and used it along with the speaker to rapidly internalize the information as they heard it.

This use of locations is why the Roman Room technique is sometimes called the Method of Loci. Loci is the plural of locus, a Latin word for a place. You have “loci” when you have strung multiple places together, such as the four corners of a room.

In the Greek tradition, we have the Story of Simonides of Ceos, which I give two powerful versions of in our detailed study of 7 Ancient Memory Palace tips.

Now, this technique is not just about using buildings or rooms. We also have the notion of space itself, which was incredibly special to the Greeks in many ways. As Thales said, a person widely considered to be both the first philosopher and scientist:

Μέγιστον τόπος άπαντα γαρ χωρεί

Megiston topos hapanta gar chorei

Space is the ultimate thing, as it contains all things.

Pre-historically, we have evidence that ancient people did not use rooms at all to create their memory tools. For example, people have used constellations to help them remember. Lynne Kelly demonstrates in The Memory Code how aboriginals used skyscapes both day and night to help them remember songs. She also shows how they used long stretches of geography and even objects like the lukasa to help them memorize the names and locations of medicinal plants.

I would go so far as to say that humanity has survived precisely because it learned to use external and internal structures as memory aids. Imagine trying to remember what kind of plants are safe to eat during a drought, versus which are poisonous. If you can’t remember, you’re dead.

Roman Rooms or Memory Theatres: Which Is Better For Memory Palace Training?

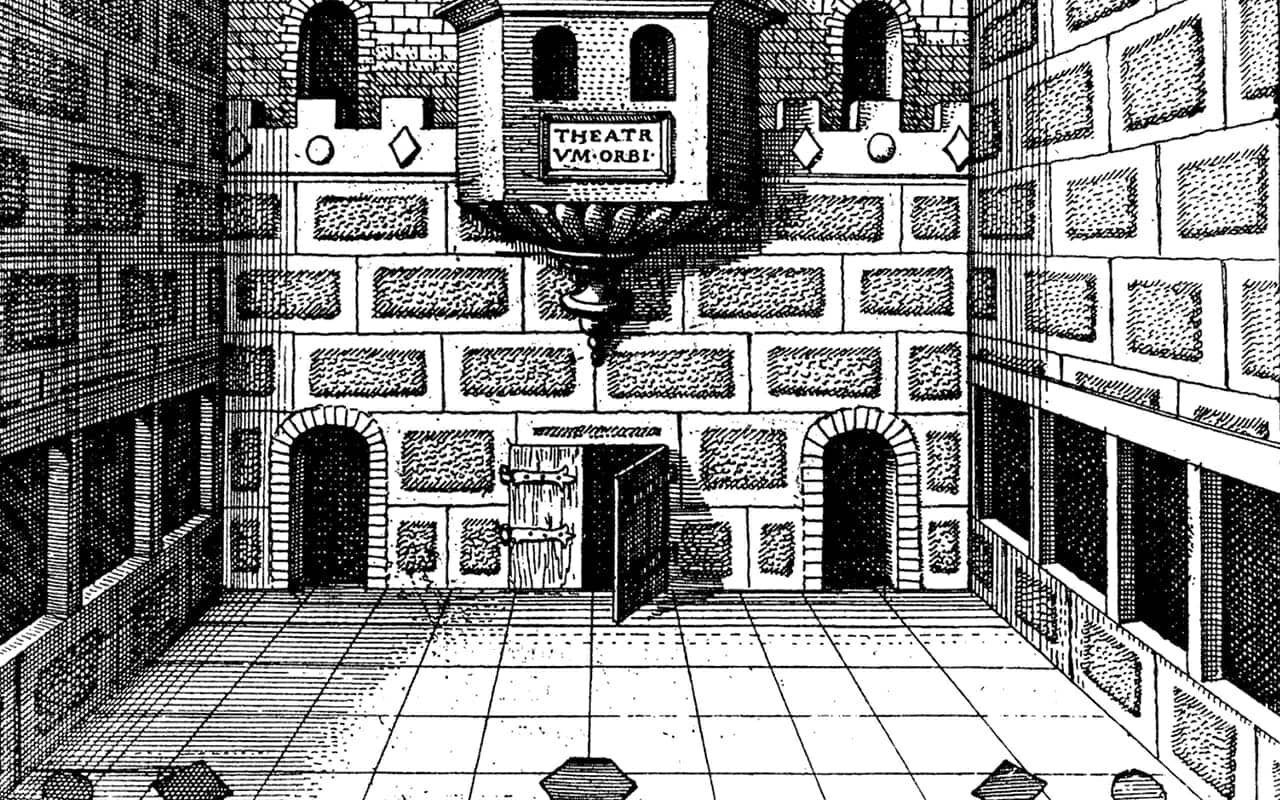

If you can’t find any terms you like, let’s introduce another option that I’m quite fond of and talk about Robert Fludd’s “memory theatre.” It uses rooms very specifically, or at least, that’s what memory expert Frances Yates believes. She talks a lot about Fludd’s variation on the Roman Room in her seminal book, The Art of Memory.

The idea here is that we can mentally visit locations, and this man is apparently imagining a structure like the Tower of Babel, an obelisk, what appears to be a town square and perhaps an angel introducing a new person to heaven.

On the Oculus Imaginationis diagram, we see different spaces that can be used in combination with other kinds of mental imagery to help us remember words, poems, mathematical formulas and names.

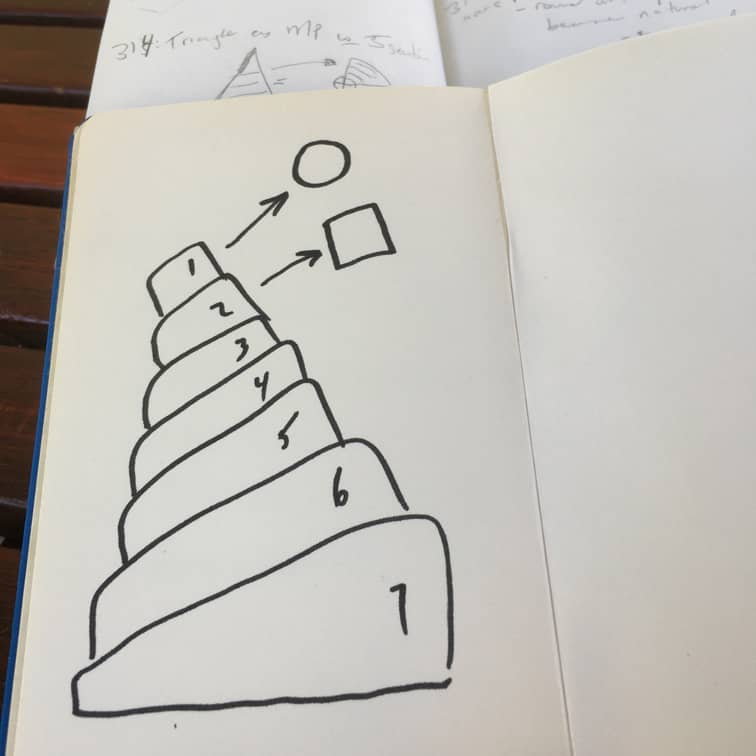

However, there is a difference to notice between ars quadrata and ars rotunda. The first is the art of using squares and the second is the art of using round and dynamic spaces, such as using trees in a forest or other shapes in nature.

As an experiment, I created my own version of The Tower of Babel and used it to memorize these two terms. On locus one, I mentally imposed a big fat circle that is badly overweight. That reminded me of the term ars rotunda. On the second locus, I imposed a square and thought of Q from James Bond bringing the secret agent into a new quadrant for ars quadrata.

Now, Fludd was apparently against using a virtual Memory Palace or any imaginary space. But that didn’t stop him from using spaces of imagination.

Who was Robert Fludd? And why should we care about his memory teaching?

He was a key thinker in the development of both scientific thinking and the use of memory techniques. He had a lively, albeit controversial exchange with Johannes Kepler, and thought deeply about the nature of the mind and memory, providing many illustrations of how he thought our mechanisms of psychology worked.

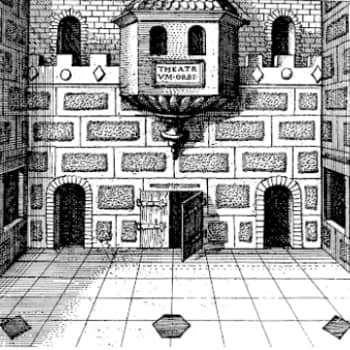

Again, it seems that Fludd preferred using actual buildings for his spatial memory work, not imaginary spaces. In fact, Yates thinks he may have used Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre for his Roman Rooms. And if you take a look at one of his diagrams, you can see that this theatre space with entrances to multiple rooms is coded in an interesting way:

Notice how the image of this theatre depicts five entrances (three on the ground floor and two on the top floor). Corresponding with these rooms are different shapes. Yates is not sure, and no one can be, but it’s easy to imagine that Fludd may have had actors stand on these shapes and then used them to walk through the rooms behind those doors.

Then, in each corner and possibly on each wall, he had pre-determined “loci” where he would place the information he wanted to memorize. We don’t know, but we can theorize that Fludd would have visited the rooms behind those doors, not imagined them. Assuming that you’re using rooms you’ve seen with your own eyes, now let’s talk about…

How To Prepare To Use A Roman Room

If you want to be a purist, you would first set a specific goal. For example, a goal might be to use this memory technique to memorize a speech, as the Roman orators would have done. But you can use this style of journey system to memorize anything else, from foreign language vocabulary and phrases to mathematical formulas.

For the vast varieties of possible memory goals and the powerful outcomes anyone who becomes a discipline of these techniques can experience, I want to correct a misconception.

It is sometimes said that memory techniques that use space are only useful for memorizing lists or what is sometimes called “unstructured” information.

This claim is not necessarily false, but it is deeply misguided about the nature of the information we want to memorize. For example, information is structured by default, isn’t it? How could it be information if it didn’t have a structure? The word information itself has multiple structures, for example.

The letter ‘I’ that begins the word is a structure, as is each letter in the word. The word has four syllables, each syllable a structure until itself. Analyzing information in this way is one of the great secrets used by memory artists to rapidly create multiple hooks and make concrete associations out of even the most concrete and abstract material.

To the true mnemonist, there is in fact nothing abstract or difficult or obscure when it comes to memorizing information. Every detail comes in the form of perceivable assemblages of multiple structures for which mnemonic associations can always be made. You just need to be trained and well-practiced.

Let’s go a bit deeper on this point:

When memorizing my TEDx Talk, on some of the locus of my Roman Room, I was able to encode 11-17 word phrases in the corner or along the walls.

This approach works because every sentence is a list. It’s just one word coming after another in a particular order. We just happen to call it a “sentence.” And the word “sentence” is just a list of letters, s-e-n-t-e-n-c-e.

It’s the same thing with a string of digits. For example, the 1200 digits of pi memorized and recited publicly by my student Marno Hermann who established himself at the top of the South African memory competition records is technically a list, and yet…

If you use this technique properly, in a way that allows you to both get the info into long term memory and recall it out of order, you can manipulate the linear nature of information.

You can use what I call “Magnetic Compounding” based on ideas from Giordano Bruno that vastly explode the potential of everything memorized inside of a Roman Room.

But that would no longer technically be a Roman Room – it would be a Magnetic Memory Palace. So let’s stick with the plot, shan’t we? Here’s how to get started with your first Roman Room:

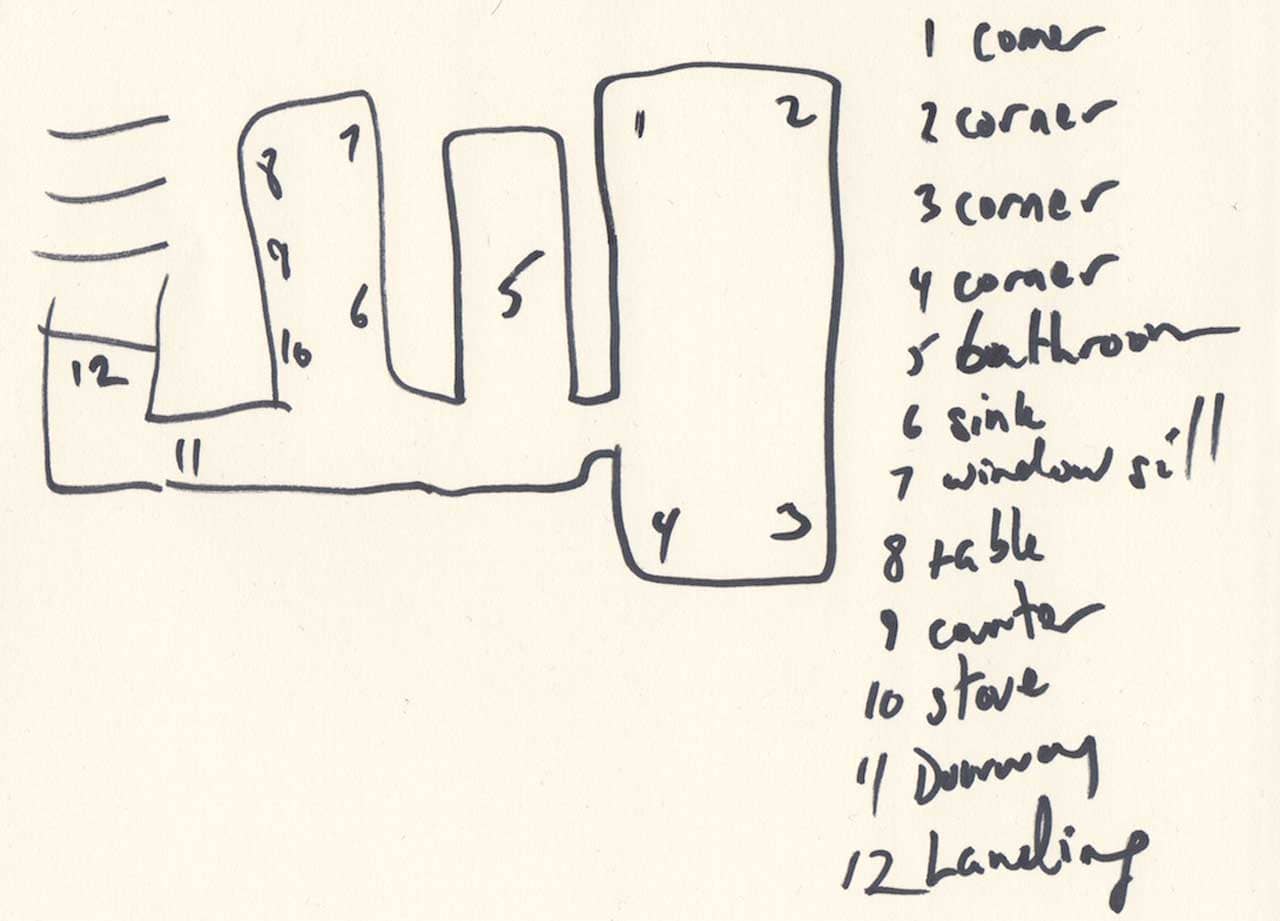

- Get out a piece of paper.

- Think of a room you’re familiar with.

- Draw the room using just four lines to represent the room.

- Represent the corners of the room with numbers.

- Write down the list of the stations.

The reason I ask students to follow these steps is not just because I have loved receiving them by the thousands as symbols of people taking action. I do love that!

But I ask serious students of memory improvement to draw the Roman Room because it helps them tap into more visual and spatial memory power than imagination accomplishes on its own. We also harness the power of something called “the levels of processing effect” by physically creating this memory aid through drawing. It then becomes newly visual to you as a blueprint, which means it’s better remembered.

Then, by writing numbers and words, you’re processing it through your numerical and verbal brain – strengthening the journey. The more levels of processing, the better, and this is true no matter how good you get. I find that if I don’t complete this quick step for both simple and elaborate Memory Palaces that I create, the technique just doesn’t work nearly as well.

I think that drawing the memory journey is like the equivalent of a London cabbie driving the streets in preparation for the exam and then taking prep tests to manually write out the routes by hand. Sure, you can probably remember the routes without taking those steps… eventually. But if you really want to succeed, you’re going to do what good students do, and compound your efforts using multiple approaches.

If you’re worried that this simple Roman Room won’t be enough space to memorize much, don’t be. Here are two mindset tips to keep in mind:

- If you haven’t developed the skills to memorize just four pieces of information in one room, why worry about thousands of pieces of information?

- Any dedicated individual who puts in the time can pull dozens, if not hundreds of rooms from their memory.

Just think about your years in elementary school and high school. Personally, from pre-school to when I graduated with my PhD, I have drawn dozens of these powerful memory tools. And that’s not to mention all the movie theatres, cafes, restaurants, churches, hotels and bookstores I’ve seen (just to name a few possible options you surely have waiting for you in your memory).

Be willing to start small, and if you’re not willing to do that, be willing to scale back after a massive effort at making enormous Memory Palaces poses too much challenge for your spatially unexercised brain. I myself overwhelmed myself like crazy in the beginning, and it seems that some of the best students do need to feel that bit of pain in order to train themselves to simplify. There’s nothing wrong with failing to follow the advice to keep it simple, so long as you learn from the experience.

How to Use Your First Roman Room: A Real-Life Example

One of the best ways to learn the Roman Room technique is to go through a real-life example.

Let’s use my February 2020 TEDx Talk and break it down into steps.

Step One: Write a Great Speech (Or Organize Your Info Well)

This step is kind of obvious, but throughout history, people have failed to do make sure their presenters are receiving the best possible message.

Even back in 90 BCE, the author of the Rhetorica ad Herennium gave instructions on how to use the Roman Room method in combination with a well written speech.

In the case of language learning, the equivalent of this step would be to organize the words and phrases you want to learn. Every minute spent in preparation will save you time later and create a better outcome.

Step Two: Select the Best Possible Roman Room

When thinking about how I was going to memorize my TEDx Talk, the stakes were high. That’s why I chose a clear and distinct location based on a place I see every day.

Then I drew it by hand. The full version, created with the help of a graphic artist, looks like this:

By figuring out each part of the Roman Room first, it is easy to start the encoding process.

Step Three: Place Your Magnetic Associations

The first line of my TEDx Talk is:

How would you like to completely silence your mind?

To memorize this line, I simply started at the first locus and thought of Howie Mandel.

Why this comedian?

Well, besides the fact that we’re both Canadian and I liked him a lot when I was a kid, “how” and “Howie” have the same letters and basic sound. Using sound-links in your choice of mnemonic images is a key part of what makes the technique work. The tighter and more evocative the images, the easier you’ll recall the information.

Step Four: Add as Much Elaboration as Needed

Howie provides just the word “how” from within this Roman Room on the first station.

To get more of the first sentence in place, I next imagined Howie chopping wood (would) while hitting thumbs up on his phone (like). Once this part of the line was encoded, I didn’t need the rest of the line because this was the point of the talk.

Step Five: Keep Moving Forward

The next step is to move to the next locus in your Roman Room.

In my case, I went from locus one in the Roman Room when I was done the first line and encoded the next line on locus two.

Sometimes I needed to encode the sentences word for word, but other times I only encoded keywords. It’s a fairly long talk, but I can often get a lot of words on one locus, so it took the equivalent of 8 Roman Rooms in total.

But again, “Roman Room” is just one of many possible names for this technique, so it’s important to not focus on the terminology. So please understand that the Magnetic Memory Method has fused all of the best techniques together into one smooth and systematic approach.

We’ll discuss some of the other parts involved in using it successfully below. First, we need to touch upon instilling the content you want to remember for the long term.

Practicing the Roman Room Method For Long Term Memory

This is the fun part of using the Roman Room method.

You see, encoding is only half of the task. You also have to practice decoding the speech using spaced repetition. Sometimes I call this process “Recall Rehearsal,” especially when I’m using Roman Rooms to memorize any speech fast.

To do that, I followed a few unusual steps that I recommend to anyone using this technique.

- Recall the speech forwards from beginning to end.

- Pick segments of the speech to practice in different orders.

- Walk the Roman Room while reciting.

Reciting the speech from beginning to end is obvious. That’s how you want to deliver it, after all.

The Secret of Non-Linear Spaced Repetition

But if you want to be absolutely flawless and have no hesitations, each part needs to really stick in your mind. If you only practice starting from the beginning, you will give the beginning what is called Primacy Effect. The end will get what is called Recency Effect.

These laws of memory, first identified by Hermann Ebbinghaus in his book, Über das Gedächtnis (about memory) show that we tend to remember best the first and last things we encounter in an information series. We forget information at different rates, creating an effect he called “the forgetting curve.”

You probably have heard a friend who can tell you how a movie begins and ends, but completely botches retelling the middle of the story. This happens precisely because of these effects.

To avoid that problem while standing in front of the audience, I recited my speech out of order so that each part received sufficient doses of primacy and recency. I know that sounds weird, but recalling information out of order is absolutely essential for establishing long-term memories as quickly as possible.

This simple process of recalling the speech out of order gives each part of the speech equal doses of primacy and recency, completely stopping the forgetting curve in its tracks.

In the end, I succeeded and delivered the speech entirely from memory, using no slides or pictures. I successfully recited each and every quote as well, thanks to the fact that each was robustly remembered. Using these patterns to practice recall is the best way to achieve that level of bulletproof delivery and remove all nervousness.

Pegword Lists and the Hook Method

One neat way you can get more out of this technique is to learn how to use the pegword method, which is sometimes called the “hook method.”

In some sense, I’m already doing this in the example I just gave. Howie Mandel became a kind of hook that carried my memory across several words.

However, if you develop a set of images for each letter of the alphabet, you can link your Roman Rooms to each letter.

For example, locus one can be the A-locus. Perhaps you have a friend named Alan or Albert who will always be standing there.

Then, if you want to memorize a line like the one from my speech, you could see him fistfighting with Howie Mandel (or some other Howard). This additional approach can be useful for beginners because sometimes it can be a struggle when you’re new to think of what images you used.

But if you know what each letter stands for, then it’s easier to remember that it was Alan punching Howie to kick-off a sentence that starts with “how” because you know Alan. Howie is just an actor on a screen who has not been able to activate nearly as much of your brain and memory.

I have a detailed example list of images that I’ve used on my tutorial about the pegword method.

How to Expand Your Roman Rooms

As mentioned, you can easily create more Roman Rooms. Most people have potentially thousands of them in their minds.

But let’s say you want to make one bigger.

Let’s look back at the Robert Fludd theater again.

You can do the exact same thing as Yates imagines Fludd did.

Let’s say that in Roman Room #1 you include 5 doors. Personally, I would encode these alphabetically.

Behind door A would be the entrance to my friend Alan’s home office. (I actually use his entire house, but just one additional room does a lot to expand into more space if you’re not ready for bigger Memory Palaces.)

Behind door B would be my dad’s workshop (his name starts with B). Behind door C, I might use one of my highschool sweetheart’s homes… sigh, Ah Charla, whatever happened to you?

Another way you can expand any Roman Room is to add the walls. Four corners and four walls = 8 loci. You could also add the floor and ceiling, giving 10. This configuration is the so-called Vaughn Cube.

Or, you can change the color or your first Roman Room and reuse it. This is very mentally taxing, which is why I discourage beginners from using the technique in The Definitive Guide to Reusing A Memory Palace.

Finally, you don’t have to stick to the corners and walls. This practice is my personal preference now because I memorize a lot of verbatim lines. But for language learning, I like to add furniture. Sometimes multiple shelves of books can be useful too, but generally the more compressed the space, the more difficult it can be to manage.

How to Modify A Roman Room

As I discussed in my writing on How to Renovate a Memory Palace, I generally discourage making changes after-the-fact. It’s time consuming and reveals that you haven’t really put enough time into planning either your Roman Rooms or your learning goal.

For example, it would have been a huge frustration and a waste of time if the rooms I used for my TEDx needed to be changed along the way.

Not only that, failing to structure the journey correctly from the beginning could have led to completely blowing the talk altogether.

If you really must modify a Roman Room after-the-fact, I suggest that you do it after all the core information has already been entered. Then, see if you can add a wall where you previously only used the corners. Or use the foot of the bed where you previously used only the pillow area.

When you get really good at this technique, you’ll find that you can get extremely detailed in your Memory Palaces. Mary Carruthers tells us in The Medieval Craft of Memory that John of Metz used every stone of the tower he lived in for his loci. He must have practiced a lot to reach that level of skill!

Is the Roman Room Method the Best Memory Technique?

Success with any memory technique you choose depends on your goal. It also depends on your current level of skill and on the nature of the information. This is as true of Roman Room memory solutions as it is of every mnemonic technique you’ll ever find.

At the end of the day, preparation matters. I suggest that beginners start with simple goals, like a handful of vocabulary in a foreign language or song lyrics.

To learn an entire language, you’re going to want to develop at least one Memory Palace Network.

If you want to deal with numbers, you’ll need to add a second technique, either the Major System or the Dominic System – both are essentially pegword methods tailored for numbers. And rest assured that they’re not new. They both descend from the Katapayadi system which we can track back to 683 CE.

There’s so much more to be said about all the memory systems out there. But the best thing to do is pick one, get started and stick with it for at least 90 days. Practice a minimum of 4x a week. No matter what approach you use, it’s consistent study and practice that we each need to become memory masters.

If you’d like more help, please sign up now for my FREE Memory Improvement Kit here:

Related Posts

- Tap The Mind Of A 10-Year Old Memory Palace Master

Alicia Crosby talks to us about how she memorized all of Shakespeare's plays in historical…

- A Polyglot Club For Memory Palace Builders

Use this resource to find great foreign language vocabulary words for memorizing in your Magnet…

- 3 Blazing Fast Ways To Increase Memory Retention

Memory retention... what the heck is it? Is it worth worrying about? If so, can…