Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

I don’t blame you. After all, there are lots of different kinds of skills that require different kinds of practice.

Not only that, but some people use a different term: dedicated practice. You might also see it called intentional practice. These variations on the term only add more confusion.

But there is an easy way to understand this concept and I’ll give you examples to make everything that goes into proper practice crystal clear.

And if you’re wondering if you need a coach or not in order for deliberate practice to work, we’ll discuss that too.

At the end of the day, deliberate practice will work for you. It’s just a matter of getting the facts straight and learning how to plan.

Since informing yourself correctly is key to practicing well, I’m glad you’re here. Let’s dive in!

What is Deliberate Practice?

The term is used often in sports science and is often defined as practicing according to specific steps or instructions.

Dedicated practice is planned, based on small component parts and improvement is meticulously tracked by capturing data. This data is then used for the individual person engaged in the practice to help them further improve by dialing down even deeper on key areas that require improvement.

For example, I study music and take courses online from Scott’s bass lessons. In one of his programs, Scott identifies 9 key areas of deliberate learning for musicians:

- Technique

- Fingerboard knowledge

- Accompaniment skills

- Theory and harmony

- Repertoire and performance

- Rhythmic development

- Chordal skills

- Soloing and improv

- Sight reading

Obviously, these areas don’t apply to all levels of skill, but the point is to break practice down into granular areas.

When it comes to how to memorize a song, for instance, you might dig even deeper into the theory component and study the modes.

You just have to self-identify where you need improvement the most and then make a plan to fill in the gaps. If you’re not able to spot these areas on your own, this is where a coach can be very impactful.

Deliberate Practice Examples

We’ve just discussed how a musician might break their practice down into several key areas.

This principle applies across multiple disciplines, so let’s have a look at a few.

Deliberate Practice in Language Learning

One of my favorite ways to apply this form of practice is learning new words and phrases in a foreign language. It works well at any stage, beginner, intermediate or advanced.

There are a few ways to apply deliberate practice theory to language learning.

First, you can make sure you hit the Big 5 skills in meticulously scheduled doses:

- Committing new words and phrases to memory

- Reading

- Writing

- Speaking

- Listening

But another way you can apply this form of practice to language learning is in how you approach memorizing phrases and vocabulary.

For example, let’s say that you’re learning a sentence in German like “Das Blaue vom Himmel versprechen.” It literally means the blue promise from the sky to indicate a promise that cannot be fulfilled.

If you find you get stuck on such phrases, a simple way to practice it more efficiently and ease it into long term memory, involves breaking it into 2-3 parts.

- Das blaue vom

- Vom Himmel

- Himmel versprechen

I tend to prefer starting in the middle and working on just two or three words in a loop. Then I add the end to create a longer loop before going back to include the beginning.

Incidentally, I adopted this approach from music, where it is very common for students to make the mistake of going back to the beginning of a song when they make a mistake. Instead, if you take a single bar and loop it in this exact same manner, you’ll help erase the mistake without having to replay the whole song.

This kind of laser-focused, purposeful practice helps make sure that you’re weeding out problem areas while allowing your brain time to process the whole.

Deliberate Practice in Painting And Art

When I taught film studies, we talked a lot about the “deep narrative” of a story, which is why my ears picked up when I read the artist Tanya J. Behrisch on the principle of “deep time” in art.

In brief, time spent in nature or plein aire vastly improves your technique. This is quite different than deep narrative techniques where filmmakers use an economy of means to create sometimes vast universes in your mind in just 2-3 hours.

The theory makes a lot of sense. For example, the more time you spend studying exactly how the light of the sun illuminates a particular shade of green on a specific kind of tree, the more likely you’ll be able to express it in ways that create both recognition and unexpected emotional impact.

How exactly do you practice deep time as an artist?

By actually using your exposure to nature to mix your paints and get them on the canvas. The artist’s sketchbook and consistent studies over time help create an observation loop as they track their progress over time. Artists can also detail the exact nature of their experiments and innovations for future reference.

As the artist Behrisch puts it, deep time is needed to learn what the environment being painted has to say. There is a physical dimension, according to Behrisch, that amounts to allowing the senses to take on the life of the environment in a way that directs the artistic choices of color, stroke, shade, perspective and other aspects of image creation.

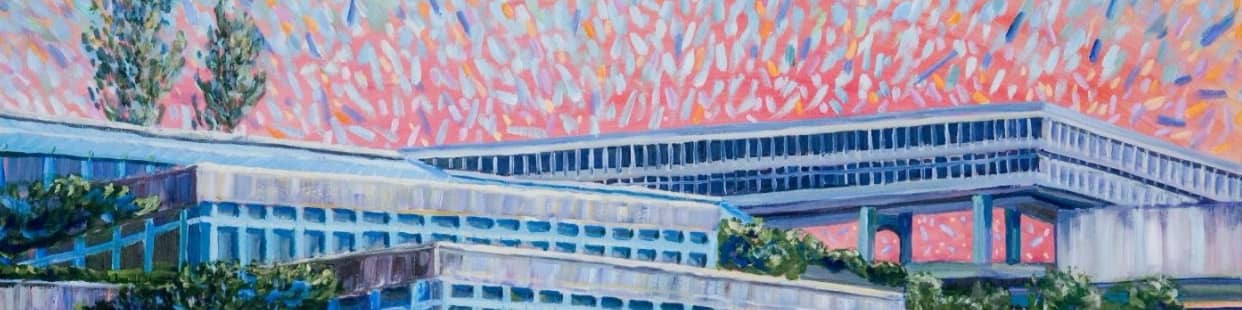

SFU Morning by Tanya Behrisch, 2008.

Deliberate Practice in Writing

I’ll never forget when Professor Leps remarked about Roland Barthes that he was a remarkable writer precisely because he wrote masterfully in so many different genres. He wrote theory, philosophy, criticism and addressed multiple disciplines.

Leps said this to a class I took at York University back in 1998 and her observation influenced me to write in as many genres as possible myself. Doing so has helped me improve as a writer for reasons we’ll discuss in a moment.

But in order to gain any level of skill in writing, one needs to develop several levels of understanding. Each needs intentional practice in order to grow one’s skills as a writer. Here are four that have been particularly important to me:

- Diction

- Genre

- Theory

- Structure

Practicing diction comes down to style, the specific words you choose to use. This requires the practice of writing itself, but also observation of how you naturally write in comparison with your observation of others.

Genre, on the other hand, requires a study of situations and various kinds of plots. For example, there are at least two kinds of tragedy.

In one, the protagonist fails to recognize his or her errors. In another, the protagonist does have a moment of recognition, but only after it is too late for correction. It takes dedicated study and actual time spent writing within a genre to begin to spot these types. Otherwise, it’s all too easy to take a genre like tragedy for granted.

Theory will help you spot these structures with greater ease. But even understanding theory can take practice. But the more that you combine study with implementation, the deeper your understanding becomes and the better you’re able to practice the craft.

Writing is also a physical art. It requires consistency over long periods of time. The first draft of my latest book project took 44 days with a minimum or 2000 words per day. I did that while continuing to write for this blog, where each article averages out to between 1700 and 2000 words. Given that I’ve written over two dozen books and hundreds of articles, I can tell you that stamina is something you build through consistent practice. No one is gifted with it from on high.

As an example of how I trained my stamina, here’s a practice I still use to this day:

I have trained myself to write for as long as one of my favorite albums takes to play from beginning to end.

For years, most of the posts on this blog were written while listening to just one album. Because I find editing extraordinarily tedious, I typically will use a separate album. A book written while listening to Nevermore may be edited while listening to Lou Reed, for example.

“Entraining” your brain to write by listening to the same music during each session could be a powerful deliberate practice technique for you.

You don’t have to take my word for that training using intentional practice matters. Stephen King says as much in his own words in On Writing and also talks about writing to music. Likewise, I learned about the importance of writing consistently from Susan Swan, under whom I studied writing at York University.

But to be as clear as possible:

I treat writing an entire book very differently than I do writing for my blog. Whereas a blog post can be drafted in an afternoon, a book may take weeks, months or even years.

Furthermore, successful blogging has certain rules and principles in order to reach audiences who typically use search engines to find answers to questions.

Books, on the other hand, go much deeper and can use a variety of structures. For example, most of my books are like manuals. But when I wrote The Victorious Mind, I practiced combining the delivery of raw instruction with scientific journalism and autobiography. I took inspiration from books like Moonwalking with Einstein by Joshua Foer and Suzanne Segal’s Collision with the Infinite.

The point is that you need to practice the principles that are related to the genre and the structure you’re creating in while allowing theory to guide your diction.

Critical Thinking and Deliberate Practice

As a final, briefer example, let’s look at critical thinking. This is an important skill that cannot develop without consistent practice.

As Becki Saltzman puts in in her LinkedIn Learning course, Developing a Critical Thinking Mindset, you need to create a practice routine that integrates this form of thinking into your daily life.

She shares that she poses one question to herself each day of the week. The question may cover:

- Issues at work

- Medical decisions

- Societal debates

- Trending ideas

She goes even deeper by dividing the kinds of questions she practices by day of the week:

- Monday = a purpose question (is my purpose properly aligned?)

- Tuesday = an information question (what are the best resources I need to look at?)

- Wednesday = a question question (what am I failing to ask?)

- Thursday = a perspective question (what perspectives am I leaving out?)

- Friday = Assumption question (what assumptions have I left out?)

- Saturday = Concept question (how can I better clarify one of my ideas?)

- Sunday = Conclusion question (how can I find better evidence to support my ideas?)

But practicing critical thinking using this structure, Salztman promises outcomes that I believe are very true:

We will make fewer mistakes and achieve intellectual humility. In other words, this form of practice keeps us open to learning more because we acknowledge that we do not know what we do not know.

For more ways to practice in this area, check out these 9 critical thinking strategies.

Deliberate Practice in Meditation

One of my favorite ways to apply deliberate practice is in mindfulness and a style of concentration meditation that is a bit more robust than other traditions.

In addition to daily sitting, this approach involves memorizing and reciting Sanskrit from a particular philosophical tradition.

Then, throughout the day, when unwanted thoughts arrive, specific statements “neutralize” them.

When pleasant mental experiences arise, deliberate practice is used to strengthen the positivity. The specific statement I make is “deepen, deepen” while focusing on the pleasant aspect.

According to renowned meditation expert Shinzen Young, this process creates a positive feedback loop. In other words, the more you label the pleasant experiences, the more pleasant experiences you have to label.

In this same discussion with Young, Leigh Brasington called the outcome of this process “Ecstatic Meditation.” He gives instructions on how to practice in his book, Right Concentration.

For more exercises that help you practice meditation intentionally, please also consider reading The Victorious Mind.

Why Deliberate Practice Works

According to Campitelli and Gobet in Deliberate Practice: Necessary But Not Sufficient, the success of deliberate practice may not come down to the amount of hours you spend on a skill. At least not entirely.

Looking at chess, they found that other factors were involved, such as:

- General cognitive ability

- The age a person begins to practice

- Handedness

- The exact season of birth (due to exposure to viruses more or less prevalent during particular parts of the year)

Don’t let these findings discourage you. The researchers focused strictly on chess, after all.

But I mention the research because knowledge can give you mental strength that leads to identifying issues and helping you find solutions.

Ultimately, the real reason deliberate learning works comes down to the neurochemistry of habit formation.

Some of the best and most accessible resources on the science behind how the brain helps you form positive habits are found in books like:

I’ve already given an example of how I’ve put this science to work in my own life. Whereas I never used to believe that I could write for a living, by simply committing to write 2000 words a day each and everyday, I completely rewired my brain. It’s now very difficult for me not to write at least that much in the same way some people crave exercise… or junk food.

I think you get the picture:

Repetition is what forms habit, good or bad. The trick is to focus on repeating the good things enough times that your brain chemistry takes over and you crave the repetition of the steps that lead to positive outcomes. Even if effort is involved, you will ultimately not have a hard time showing up to do what works.

And on those days when you still struggle, you’ll have metacognitive tools provided by intentional practice itself that will help you “troubleshoot” the issues and neutralize them.

How to Use Deliberate Practice to Master Anything

Now let’s get into the good stuff: Exactly how to apply deliberate learning to the skills you want to learn.

Although there’s no perfect way to order the exact steps involved, I’ve been practicing presenting information in logical order. But this is where learners sometimes get hung up:

You don’t necessarily have to execute anything in the exact order it’s presented. Once you have the bird’s eye overview, recreate the steps in the manner that makes the most sense for you. And if things don’t work out, come back to the training and start again. As you’re about to discover, reviewing your steps through critical observation is a huge component of your success.

Know the Key Components of the Skill

Although a skill like archery might look like one swift moment when practiced by a pro, it’s actually the combination of multiple small moves.

In order to practice effectively, you need to identify those small moves and work out ways to practice them as independently as possible. In painting, it might be devising color mixing from outlining shapes. In music, it might be differentiating rhythm studies from learning the exact notes in a scale.

The more you can map the territory into its component parts, the easier it will be to navigate the whole.

To give you another example, in the Magnetic Memory Method Masterclass, I help people focus on the Memory Palace technique first. Then we move into visualization skills related to association before linking them back to the initial technique. In this way, we establish one foundation at a time and then go back and strengthen that initial foundation through a process of review.

Plan Based On the Components

Once you’ve identified all the different parts that are involved in a skill, create a plan of attack. As we saw with the critical thinking example, Saltzman spreads her practice across the entire week.

You can also refer back to the method of splitting things up that I shared in the music and language learning examples. Instead of tackling a whole piece, you can look at just parts of things on specific days.

For example, I often teach my serious memory students to prepare what they want to memorize early in the week, practice encoding it during the middle of the week, and then practice decoding the information during the end of the week.

Obviously, this particular suggestion can be modified in different ways. If you don’t want to split the sessions across an entire week, you can split them into morning, afternoon and evening. Experimenting to see what works best for you is the fastest way to settle on a strategy that provides consistent and substantial results.

Embrace Discomfort

There’s a reason many experts say that you have to get outside your comfort zone. Taking action not only requires energy and focus, but you also can never be sure that the expenditure will pay off.

That’s why it’s important to let go of the outcome. Perfectionists have an especially difficult time doing this, and they often benefit the most when they’re finally able to let go of control. The reality is that no one can actually control anything that’s going to happen in the future, so the sooner you accept this unsettling fact, the sooner you’ll benefit from practicing without concern for how the session will go.

That said, you still need to monitor your practice. As you do, simply observe any discomfort. Label it, but do not judge it.

If you need help with this step, here are two questions you can ask if and when negative thoughts about your practice results arise.

Capture and Analyze

When I taught at Rutgers, my boss Dr. Spellmeyer gave me one of the most useful tips I’ve ever encountered. He said to never make more than three corrections on an essay I was marking.

The reason why is that too much feedback overwhelms students and prevents them from perceiving the value of what you’re offering.

Since that time, I myself have asked my own teachers to limit their feedback to just three corrections, especially in language learning. This area in particular requires a lot of courage, especially when it comes to speaking practice. If you’re interrupted constantly while trying to speak, it can shatter your confidence.

For this reason, I suggest you apply the three-corrections rule to yourself as well. The catch is that in order to find areas for correction, you need to actually capture your practice.

Fortunately, that’s easy these days. Back when I started magic, I used to record myself with a camcorder, which meant having to hook it up to a TV in order to watch the footage. But these days, it’s easy to use my desktop, laptop or phone to get instant feedback.

Likewise, anytime you meet a tutor on Zoom, there’s a one-click process to get the session recorded. It’s easy to review the material multiple times so you can analyze your own errors.

Just don’t overdo it. Try to focus on only three things at a time and you’ll give yourself space to work on the big issues. You’ll have great mental clarity for the granular details on your second pass.

Work in 90-day Blocks

Although I’m sure it’s influenced by all the years I spent attending semester courses at university, I think there’s a lot to be gained by practicing in 90-day blocks on particular skills.

For one thing, a lot of the neuroscience resources I shared above show that 90-days is a kind of sweet-spot for habit formation.

To help portion out these blocks of time, I have found The Freedom Journal useful. The best part about a tool like this is that after using it once or twice, your brain is well-trained to repeat the process without relying on an external device.

Rest Like A Pro

As the cliche goes, all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.

This phrase is instructive because not all of us feel rested by sitting around doing nothing. Some of us get our rest by engaging in alternative activities that help us express our skills in different ways.

Alex Soojung-Kim Pang brings this point out in his book Rest. I took two of his suggestions to heart and combined them:

- Take a sabbatical

- Apply your skills to something else entirely

I mentioned earlier that my latest book project took 44 days. But I didn’t mention that it was not about memory – at least not directly. I wrote a novel instead.

Although it still took energy and focus, I felt remarkably refreshed at the end of each writing period for the reasons Pang uncovered in his research. The skill of writing is being exercised, but in a completely novel way. This makes the activity as restful, if not moreso, than if I’d done nothing at all.

But whatever you do, it’s important to know what counts as restful for you. And it would be remiss if I didn’t point out that rest itself must be studied and practiced with intention and structure.

Miss Out on Intentional Practice At Your Own Risk

As I hope you can tell by now, you have every reason to practice with focused intention. There’s literally nothing to lose.

True, practicing in the ways we’ve discussed today requires setup and review. This process must also be repeated as you make your way on the path of mastery.

But isn’t this precisely what mastery is?

When I use the term “memory master” on this blog, what I mean is precisely that: the person who consistently practices their memory with no concern for the outcome.

Yes, there’s the paradox that we need to observe the outcome in order to improve over time. But life is full of contradictions, and learning to accept them is part of how we make progress. You can learn to let go of the outcome and analyze it all the same.

And if you’d like help with this process when it comes to memory improvement, give this FREE Memory Improvement Kit a try:

It will reveal the secrets of how everyone from ancient learners to contemporary memory athletes learn faster and remember more.

You’ll learn exactly what needs to be practiced and how to document your journey so you can improve your results over time.

And let me know in the comments:

What outcomes do you want and how willing are you to put the key characteristics of deliberate practice to work in your learning life on a scale of 1-10?

I am a fiction writer, intermediate level, and I’m not getting how one should divide one’s time between deliberate practice and sitting down at the keyboard and writing the story as it comes. Obviously I shouldn’t be worried about perfecting my dialogue and so forth the first time I sit down and write a scene, but how much time should one develop to working on the craft, as opposed to just writing? There are so many craft books out there, filled with exercises, some of them quite excellent, but to devote time to them eats up “writing time.” Is there some kind of guideline? Maybe this sounds stupid, but I really wish I could come across advice like, “Spend 1 hour working on craft for every 6 hours you spend writing your story.”

Thanks for this post.

I’ve written many books in my career and would suggest that sitting down to write is itself deliberate practice and there is no answer to the “how long” question. It’s always a case-by-case basis and a lot depends on your understanding of what needs to be in each scene to tell the story relative to your audience.

To give you some examples, which include reading books on the craft as part of dedicated practice and never something that “eats” writing time, when I wrote Flyboy, my first “Memory Detective” novel, I spent two months reading twenty Michael Connelly novels and thinking a lot about my former career as a Film Studies professor and story consultant.

The first draft was 44 days straight of between 2-4000 words per day. I took no breaks.

The second draft up to the 22nd draft is a much longer story, each of which requires its own definition of what one can call deliberate practice.

So, how long did it take? It took my entire life looked at one way, it technically didn’t need me to read novels in the genre, but it was certainly part of the journey. What mattered was that I wrote every day to meet a word minimum. I rarely struggled to reach the 2k minimum and usually exceeded it.

Flyboy has been a hit with the people I wrote it for and the sequel is about 1/2 done. Then there’s a spin-off series that is about to be released, and yet another first book in another series has already been drafted.

I also have recently finished the first draft of another memory training book, and the same principle applies:

It’s not about how much time it takes. It’s about having minimum word counts, at least in my case. I’ve only ever heard one writer speak against word count minimums, and frankly, I don’t believe him. He says he only writes when he feels like it, and if that’s true, then I have no explanation for the volume he produces. But given the context of where he said this (in a marketing piece to sell his course on writing), I’m pretty sure it was advertising BS.

As for “craft,” I would suggest defining very closely what this means to you. It might mean something completely different to me than it does to you, and in many cases, the real craft is making it invisible so people forget they’re reading at all.

Personally, I’d say that one works on craft by combining reading with writing and thinking. And writing is always re-writing, so I’d suggest thinking of writing as life and an activity quite outside the numbers game of time, but definitely inside the numbers game of how much material we wring out of life and then re-wring through editing to produce something great.

Does this way of looking at things help you out?