After completing a BA, two MAs and a PhD, I have a feeling that you’ll find my knowledge of how to take notes from a textbook effectively very useful.

After completing a BA, two MAs and a PhD, I have a feeling that you’ll find my knowledge of how to take notes from a textbook effectively very useful.

Not only that, but I’ve earned a variety of certificates. I’ve passed language exams in German and Chinese.

I even have certifications in everything from hypnosis to my security guard license from back when I worked as a store detective.

Would you like to know how to takes notes while reading from someone equipped with this many learning experiences?

If so, I promise that your textbook notes will be stellar from now on. You’ll remember so much more just by adopting these strategies.

Ready?

Let’s dive in!

How to Take Notes from a Textbook: My Proven Process

As you go through this tutorial, here’s something important to understand.

Learning requires variety. Studies in active recall have demonstrated this fact many times.

I’m going to give you one of my favorite strategies for introducing variety into your note-taking activities. I just want to set the stage from the outset.

It’s not that I use only one approach for reading textbooks and memorizing their content. It’s a combination of several.

Don’t worry. They’re fun and easy to mix and match. And switching things up is part of what makes the strategy so effective.

One: Prime the Textbook

When I first started university, I used to read textbooks from cover to cover.

The only problem was, I never took a moment to actually read the covers. Nor did I bother with the index, the table of contents or the colophon page.

Each of those features are packed with detail that help your mind start to form a mental picture of what the book is about.

And that’s the first note I take using the Zettelkasten method. Using an index card, I jot down the author, title and usually the date of publication with the name of the publisher. Like this:

I know that this might seem like overdoing it. But if you want to be polymathic, it helps to know the names of the books you read.

Two: Take A Picture Walk

In Learning How to Learn, Barbara Oakley recommends taking a few moments to go through each textbook you read to look for charts, pictures and diagrams.

Technically, this accelerated learning technique belongs to priming.

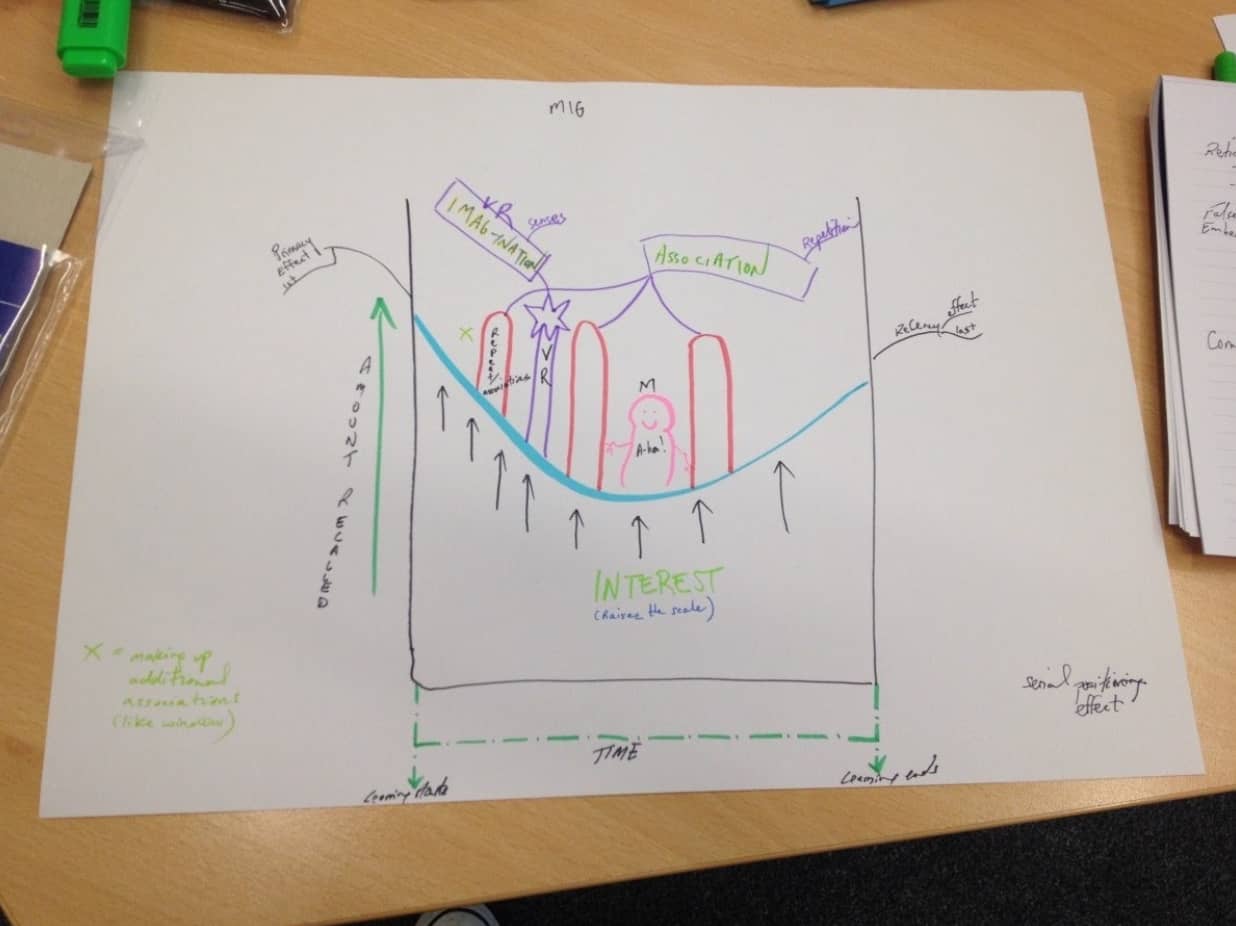

The key difference in how I use the technique is that I’ll often sketch out the diagrams I know I’ll find useful by hand.

For example, when I was learning about spaced repetition, I rapidly committed the information to memory by drawing this graph related specifically to the serial positioning effect:

Personally, I feel like this is a kind of visual note-taking. I highly recommend it, especially if you struggle with understanding graphs as much as I sometimes do.

Three: Make Your Notes Manipulable

I rarely use notebooks when reading textbooks. Instead, I use the advanced flashcard strategy Professor Lesley Higgins taught me at York University. It’s a form of active reading that many people tell me they wish someone had shown them long ago.

I wish I’d had these tactics earlier too! Especially when Professor Higgins stressed the importance of why using index cards instead of notebooks is so important. It’s because using cards so much easier to manipulate your notes later.

Boy, was she ever right!

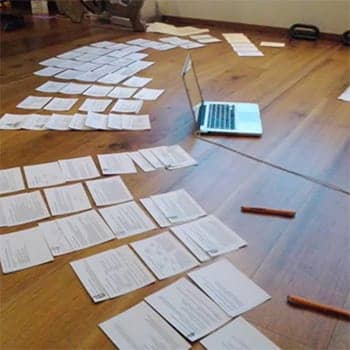

When it came time for me to write my dissertation, I saved countless hours of time by spreading all the notes I’d taken from dozens of books across the floor. I cleared the entire living room and arranged my outline instead of writing it.

This process also allowed me to easily arrange all the cards into a shoebox. That way, I didn’t have clutter all over the place. And anytime I needed to look anything up, all my notes were arranged by author, just as if I had a professional library.

Four: Don’t Worry Too Much About What’s Important

A lot of people have asked me over the years I’ve been writing this blog about how to know what counts as a main point.

It’s a good question, but not an essential one.

Most good books spell out what’s important and isn’t. In the case of textbooks, they usually include breakout areas for summaries and use bullet points.

You can also take extra care to re-read introductions and conclusions and review the index. That’s what an index is: a categorization of the book’s main points and important references.

And the beauty of extracting notes using the index card method you’ve just discovered is that you can easily set cards aside that you don’t need and shuffle them back in later.

Rest assured: you’re not wasting time by taking notes you ultimately won’t use. As my friend and fellow memory expert Lynne Kelly puts it, the hand is the ultimate encryption device. For this reason, it’s okay to take notes with abandon.

Five: Build Your Own Index

If you own your textbooks and don’t mind writing in them, here’s a technique I don’t use all the time. But remember when I said it’s useful to have variety and mix in different techniques?

That principle is related to a proven learning method called interleaving.

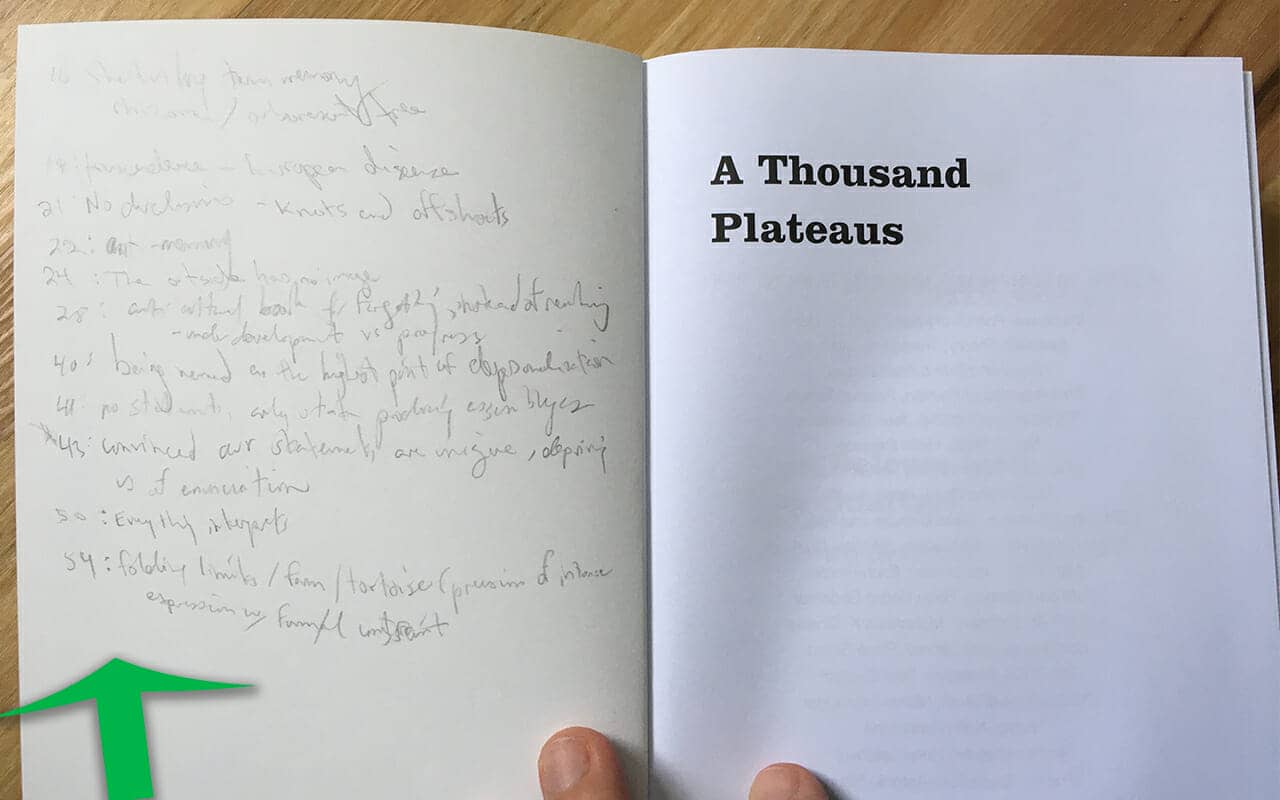

Part of how I interleave involves sometimes not taking notes externally, but writing them into the book itself. I don’t underline or write on any of the pages, however.

Instead, on the inside front cover, I put the page number and concise note to remind me of what point I found interesting on that page. Here’s an example:

Six: Use Science-Backed Review Processes

Taking notes is just part of what it takes to usher information into long-term memory.

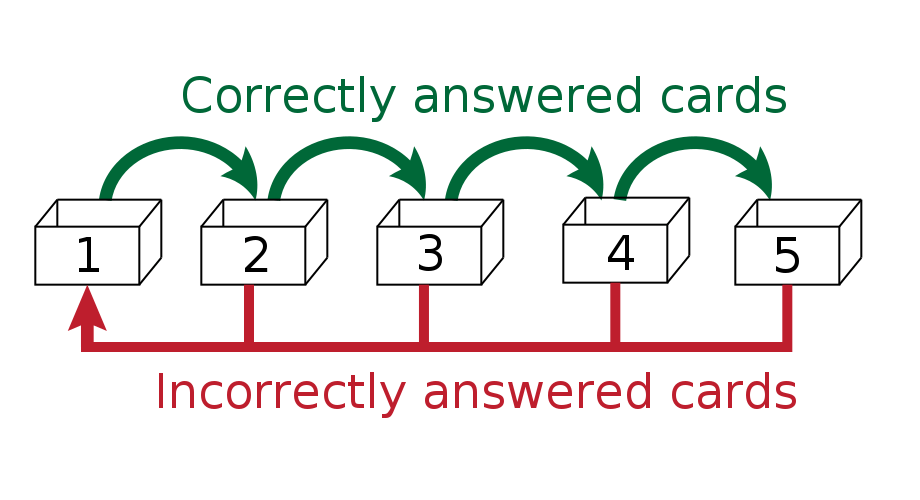

When it comes to rapidly absorbing textbook information, I suggest you use a Leitner box. This technique only works if you’re using cards in the way I’ve suggested. Using the shoebox pictured above, I rotated my notes in a review pattern that looks like this:

You are simply reviewing the cards and seeing how many you get right. This approach is a highly optimized version of what Anki does, minus the problems created by digital amnesia.

Seven: Include The Memory Palace Technique

With the principle of interleaving in mind, switch things up by sometimes memorizing information using the Memory Palace technique.

Let’s say you need to memorize a list of facts. This ancient memory technique lets you create a mental journey and place associations in familiar locations.

Later, you think back to those mnemonic images and they help you remember the target information.

Eight: Write Summaries

Keeping in mind that using your hand builds your memory, take a few moments each day to write 250-500 word summaries of what you’ve read.

A recent study has shown that writing leads to many more brain connections than typing. Even the founder of a recent writing app agrees that handwriting is ultimately better all around for learning.

That said, I’ve typed a lot in my career. It’s not as if typing up notes is completely bereft of learning power. It’s just shown to perform incredibly poorly compared to typing.

Deadly Mistakes To Avoid

Whenever exploring learning strategies, keep an open mind. But always use critical thinking too.

For example, I’ve heard people say that you should never copy entire quotes.

Really? I’ve copied hundreds of quotes and it has never hurt me. Quite the opposite. It’s helped me learn faster and remember more.

It’s also important to avoid overthinking things and getting caught up in perfectionism. These issues only lead to procrastination.

Learning requires action and you will gain so much by exploring and experimenting with a variety of techniques.

Other mistakes include:

- Making your pages confusing by using colored highlighters

- Taking obscurely worded notes you can’t understand later

- Not explaining what certain symbols mean (which come up a lot in math, chemistry, logic, etc.)

- Failing to read the book carefully because you’re in a rush

- Not planning your time in advance

- Not having a quiet study area

- Studying while tired, malnourished or dealing with unattended brain fog

How to Remember Your Notes Once And For All

As we’ve seen, there is no one method. Rather, it’s important to combine several.

It’s also important to understand what people are telling you. What you’ve learned today applies specifically to textbooks and other materials read for study purposes.

Although having my notes locked up in journals and notebooks has never helped me, that doesn’t mean I don’t use them. I journal frequently, in fact.

The point here is that when I’m studying textbooks, I apply a deliberate practice to the process I’m so blessed to have learned from a world class scholar.

And now that knowledge has been passed on to you.

If you’d like more powerful tips and tactics, I invite you to get my free memory improvement course:

It will help you continue your journey and give you more insight into how to use the Memory Palace technique discussed above.

Enjoy taking notes in a much more sophisticated way in the meantime and just shout out through my contact page if you have any questions. Or leave a comment below.

Go for gold!

Related Posts

- Stoic Secrets For Using Memory Techniques With Language Learning

Christopher Huff shares his Stoic secrets for using memory techniques when learning a language. You'll…

- The German Professor Who Defends Memory Techniques for Language Learning

This professor defends memorization techniques for learning foreign languages and has the science to prove…

- The Memory Journal For Competition and Developing Mnemonic Systems For Learning With Johannes Mallow

Johannes Mallow shares details on how he used a Memory Journal to massively improve his…