Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

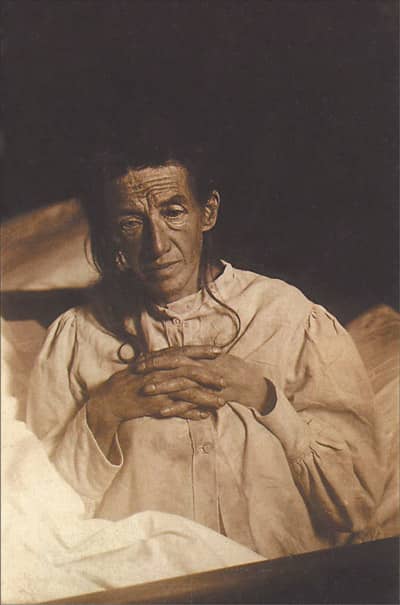

Eventually, he could not cope with her hallucinations and forgetfulness that often kept him up all night. When Auguste was 51, Karl placed his wife into a psychiatric institute.

There, she spent the rest of her short life, eventually dying at the age of 55.

Auguste is now acknowledged to be one of the most well known patients in medical history (Muller et al. 2012).

The doctor who examined her, Dr. Aloysius Alzheimer, named the disease for which she is acknowledged as the first identified patient. At that time, he called it “presenile dementia,” but later his colleague Emil Kraepelin gave the condition the name by which we know it now.

It’s been over 100 years since Alzheimer’s disease was first described, and yet, no cure has, as of yet, been found. However, with an increasingly aging population, it has become more pressing than ever to find effective treatments (Giacobini and Becker, 2007).

In the absence of a definitive cure, this post and podcast will provide important information about Alzheimer’s. The disease can be all-consuming for those afflicted, as well as their caregivers. Understanding how it works and how to care for that person may help to relieve stress for those trying to cope.

Who Does Alzheimer’s Affect?

Alzheimer’s is a disease of old age, and generally, affects those over the age of 65. However, a rare variation of the disease, early-onset Alzheimer’s, will affect those as young as 35. The prevalence is higher in females than males, although females do tend to live longer, which may explain this trend (Keene, Montine and Kuller 2015).

It’s important to realize that although Alzheimer’s affects older adults, it is not part of normal aging.

Right now, the overall prevalence of Alzheimer’s is between five to seven percent throughout the population (Keene, Montine and Kuller 2015). As we age, the likelihood that we will be affected by Alzheimer’s nearly doubles every decade. That is, by the ages of 95-99, your chances of having developed Alzheimer’s increases by 50%.

What Causes Alzheimer’s?

The cause of Alzheimer’s is, as of yet, not completely understood (Ginter et al. 2015). We do know that genetics plays a role in early-onset Alzheimer’s. This form of the disease is rare, and affects people under the age of 65. What genetics fails to fully explain is the prevalence of Alzheimer’s in aging adults (Keene, Montine and Kuller 2015).

The links between risk factors and Alzheimer’s have not fully been proven. However, in studies the following has show to possibly increase our risk of Alzheimer’s:

- Hypertension (high blood pressure) during midlife

- Having Type 2 diabetes

- Poor diet or otherwise not eating foods that improve memory

- Obesity

- Living an inactive lifestyle

- Having had a brain trauma

- Having had exposure to secondhand smoke

If you have a family history of dementia and Alzheimer’s, the chances of developing it yourself is much higher. People with a first-degree relative (parents or siblings) who developed dementia after 65, but before 85, have a higher risk factor. In fact, they are 10 to 30 times more likely to develop dementia themselves (Keene, Montine and Kuller 2015).

Alzheimer’s and Memory

Alzheimer’s is the most common cause of dementia, which is a degeneration of cognitive function (thinks like fluid and crystal intelligence. One of the earliest and most distinctive aspects of Alzheimer’s is its affect on memory.

The first warning signs a doctor and other caregivers will look for is memory impairment (Wolk and Dickerson 2015). The patient will typically go through selective losses in short-term memory.

For example, a person suffering from the early stages of Alzheimer’s may find themselves getting lost on familiar paths. They may forget recent events and repeatedly ask for the same information.

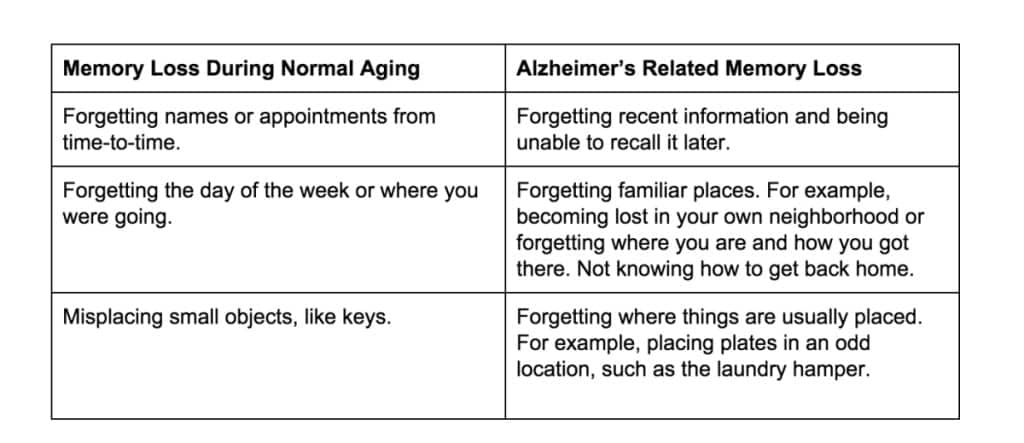

It’s important to keep in mind that normal aging does accompany some memory deterioration. However, unlike normal aging, the cognitive decline associated with Alzheimer’s comes in the way of normal daily activities.

The table below compares normal memory loss associated with aging to memory loss associated with Alzheimer’s (Leifer 2006).

Family members may notice these types of memory declines and others, such as repeatedly asking for the same piece of information.

As the disease progresses, memory becomes severely affected. Memories of the person’s life are impacted. A patient will forget important life events, occurring at a particular time and place early on in their disease (Wolk and Dickerson 2015).

Moreover, factual memory, such as the words used for objects and concepts, deteriorates as time goes on.

A doctor may test memory by asking patients to learn and recall a series of words or objects. Recall is asked for both immediately and at a delay of five to ten minutes. They may also ask them about important historical events or artifacts in popular culture (Wolk and Dickerson 2015).

The brain of a normally aging person will compensate for the memory loss due to normal aging, especially if they meditate for memory and concentration. The cognitive decline of a normally aging brain will not be severe enough to affect their ability to complete everyday tasks. Nor will the cognitive decline affect a person’s ability to live independently (Wolk and Dickerson 2015).

However, a brain with Alzheimer’s will decline quickly. This can vary, but the average survival rate after diagnosis is between eight and ten years. Some survive for as long as 20 years after the diagnosis (Wolk and Dickerson 2015).

What Alzheimer’s Looks Like

As Alzheimer’s progresses, the afflicted person will become more and more disoriented. Alzheimer’s patients will increasingly be unable to:

- Speak or write coherently. They will have trouble finding the right words for the right situation.

- Understand what is said or written.

- Recognize familiar places.

- Plan how to take multi-step actions.

- Carry out multi-step actions, such as cooking.

- Concentrate.

- Weed out distractions.

- Make logical choices or decisions. For example, dressing in a outfit with oddly matched colors and patterns.

As the disease progresses into later stages, the person will start to exhibit more personality and emotional changes. These can be particularly stressful. They may include:

- Increased hostility or increased passivity.

- Hallucinations or delusions.

- Disorientation.

- Incontinence.

These changes might be due to chemical imbalances in the brain. They may also be due to the individual’s increasing fear and confusion because they do not understand their own surroundings.

Eventually, an Alzheimer’s patient will literally forget the more fundamental tasks, such as how to move. They will become immobilized and require assistance for bathing, eating and dressing.

Treatment options

There is no cure for Alzheimer’s. Current drug treatments only slow the disease in the short-term, for no longer than a year. However, for patients with early stages of the disease, medications can improve their cognitive function. These benefits may need to be weighed against the medication’s side-effects as the disease progresses.

In addition to medication, there are behavioral treatments available. For example, speech therapy can be combined with medication to help patients with troubles in this domain.

Caring for an Alzheimer’s Patient

Caring for people afflicted with Alzheimer’s is a very cumbersome task, and difficulties range from financial to emotional stress. In a study carried out in the UK, nearly two-thirds of people caring for Alzheimer’s patients were family members (Beinart et al. 2012).

When dealing with Alzeheimer’s, it’s important to seek support from extended family members, friends and your community.

Ask your doctor to refer you to a local chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association.

Many changes will need to occur in an afflicted person’s home and life due Alzheimer’s. They will likely be unable to drive, and will need monitoring and help with basic tasks. These include things such as cooking and taking medications (Alexander and Larson, 2015).

Other tips for helping people with Alzheimer’s include:

- Simplifying choices, such as wardrobe choices, to reduce their indecisiveness and confusion.

- Having familiar objects or photos may help with a patient’s disorientation with time and space.

- Keep distractions and noise to a minimal so as not to agitate the patient.

- Speak clearly, with short and concise sentences to increases your chances of being understood.

- Encourage daily exercise, such as daily walk, to maintain physical health and tire the patient out. This will help prevent them from wandering and getting lost.

- Avoid major changes in their environment.

- Try to be patient when waiting for responses and actions to be performed.

- Employ safety measures in the home, such as locking medicine cabinets, removing electrical appliances from the bathroom, installing grab bars in the bathroom, and setting the water heater below 120ºF

- Install locks on the outside of the doors, so the patient cannot unlock and leave the house.

- To prevent the person from getting lost, employ the use of a “safe return program” provided by the Alzheimer’s Association. They offer 24-hr assistance.

- Try to implement a daily routine, but remain flexible.

These 11 memory strategies might help too:

In the mid-to-late stages of the disease, it may become impossible to care for the person at home. They may require skilled health care attention and placing the patient in a nursing home may be the best option.

Most importantly, remember that as a caregiver, you require care as well. Using respite services, such as adult day care and hiring home aides when possible is a great way to recharge. Caring for a person with Alzheimer’s is a marathon, not a sprint. You need to ensure that your mental and physical health is tended to.

Emotionally and mentally, it’s important to try to focus on the positive. Try to enjoy the remaining qualities and activities with your relative instead of only remembering what you’ve lost. Remind yourself that you are doing your best in moments when you feel overwhelming guilt or fatigue.

Future Hope for Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is a tragic sickness, and poses an enormous financial burden on society at large. Paying to care for patients with dementia and Alzheimer’s is predicted to cost 1.2 trillion dollars by 2050.

The good news is that there is increasing evidence that Alzheimer’s may be more of a lifestyle disease than previously acknowledged.

Except for rare cases of early-onset Alzheimer’s, which have a strong genetic component, lifestyle may determine your likelihood of developing it. That is, maintaining a healthy diet and doing regular exercise can decrease your chances of developing Alzheimer’s. Due to the strong link between blood-sugar levels, some scientists have even started calling Alzheimer’s “Type 3 Diabetes” (De la Monte and Wands, 2008).

Not everything in life is within our control. However, living a healthy and balanced life are ways to counteract the effects on cognitive function, especially as we age.

For our purposes, the question is …

Can Mnemonics And Memory Palaces Help?

It’s too soon to tell, but I highly recommend watching this TEDTalk with Kasper Bormans for an introduction to what might be possible using Memory Palace science to solve the issue:

Further Resources and Reading

Nelson Dellis spoke on the Magnetic Memory Method Podcast about his experiences with Alzheimer’s and his efforts to combat the condition. Check out Extreme Memory Improvement to learn more.

These memory tips from Dr. Gary Small may not be the ultimate prevention against Alzheimer’s, but they are going to serve you well. Give it a listen.

I recommend subscribing to Preserving Your Memory Magazine, put out by the Fisher Center For Alzheimer’s Research.

And for more information, follow-up on the following articles:

Alexander, M., Larson, E. B., Patient information: Dementia (including Alzheimer disease) (Beyond the Basics) Up To Date (2015). Online.

Beinart, N. Weinman, J., Wade, D., & Brady, R. “Caregiver Burden and Psychoeducational Interventions in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review.” Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders EXTRA 2.1 (2012): 638–648. PMC. Web. 15 Jan. 2016.

De la Monte, Suzanne M., and Jack R. Wands. “Alzheimer’s Disease Is Type 3 Diabetes–Evidence Reviewed.” Journal of diabetes science and technology (Online) 2.6 (2008): 1101–1113. Print.

Keene, C. D., Montine, T. J., Kuller, L., H. “Epidemiology, pathology, and pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease” Up To Date (2015). Online.

Müller, Ulrich, Pia Winter, and Manuel B Graeber. “A Presenilin 1 Mutation in the First Case of Alzheimer’s Disease.” The Lancet Neurology (2012): 129-30. The Lancet. The Lancet. Web. 13 Jan. 2016.

Leifer, B. P. “Alzheimer’s disease: Seeing the signs early.” Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners(2009) 21: 588–595 Web. 13 Jan 2016

Ginter, E., V. Simko, D. Weinrebova, and Z. Ladecka. “Novel Potential for the Management of Alzheimer Disease.” Bratislava Medical Journal BLL (2015): 580-81. Online.

Giacobini, E and Becker, RE. One hundred years after the discovery of Alzheimer’s disease. A turning point for therapy? J Alzheimers Dis (2015): 12, 37-52

Wolk, D. A., Dickerson, B. C. “Clinical features and diagnosis of Alzheimer disease” Up To Date (2015). Online.